Beyond Promises: Hardwiring Real Outcomes—and Cross-Border Climate Risk—into Sovereign Credit Ratings

Input

Modified

Credit ratings focus too much on climate promises rather than actual outcomes Droughts, heat, and supply-chain shocks strain economies and public finances Agencies must incorporate measurable climate impacts into sovereign ratings

In 2024, Europe experienced its hottest year, with climate disasters costing over €77 billion in 2023. The US faced 27 weather disasters in 2024, each over $1 billion, setting a record. CO₂ levels rose to 422.5 ppm, 52% above pre-industrial levels, showing emissions still increase risks. The ECB warns that water shortages threaten nearly 15% of euro area economic output. By summer 2025, low Rhine water levels disrupted transport, raising freight costs until rain eased conditions. These interconnected pressures affect agriculture, manufacturing, and services, crossing borders and impacting economies. If ratings focus on plans over results, they will undervalue this century’s major macroeconomic risks.

From Pledges to Performance—and Why Timing Matters Now

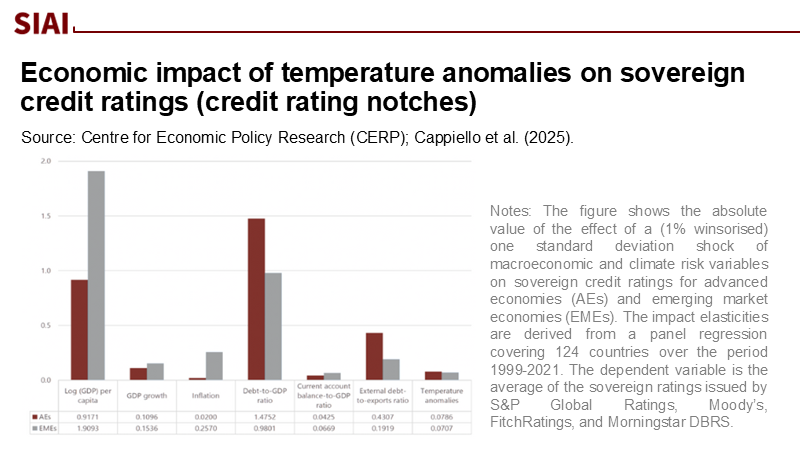

The central argument is straightforward: credit ratings should prioritize what countries have demonstrably achieved in terms of resilience and decarbonization, rather than focusing on what they have promised to do. Recent empirical work shows agencies have begun to reflect physical risk in ratings and, post-2015, to “reward” more ambitious emissions targets and lower emissions intensity. Yet the same research finds effects remain small in magnitude and that transition variables are inconsistently embedded. The policy urgency is not abstract. Europe’s documented water stress and heat extremes translate directly into sovereign fiscal arithmetic through disaster relief, adaptation capital expenditures, yield losses, and supply-chain disruptions that suppress tax bases. When Rhine levels stall bulk cargo, the shock propagates into chemicals, steel, autos, and export logistics—exactly the channels that determine medium-term debt dynamics. Ratings that lean on intentions rather than verified adaptation capacity and real-time exposures will underprice default risk and over-allocate capital to vulnerability.

What the Data Say: A Tightening Vice of Physical and Fiscal Risk

The European State of the Climate 2024 documents intensifying heat, drought, and glacier loss, with 2024 the warmest year on record across datasets. The European Commission and ECB estimate drought already costs roughly €9 billion annually and warn that up to 15% of euro-area output is exposed to surface-water scarcity, a figure that aligns with World Bank analysis projecting that inaction could shave as much as 7% off EU GDP under high-warming scenarios. These are economy-wide effects, not sectoral footnotes. Agriculture bears the brunt first—olive oil and wine yields in the Mediterranean, for instance—but the second-round effects hit manufacturing through disrupted inputs, curtailed hydropower, higher transport costs, and forced downtime. In 2025, repeated low water on the Rhine again constrained barge loads at Kaub; days later, normal levels briefly returned with rain—an illustration of volatility that complicates budget planning and warrants explicit treatment in sovereign risk models. When such swings become common, “rare events” stop being idiosyncratic; they become core drivers of fiscal stress and, consequently, ratings.

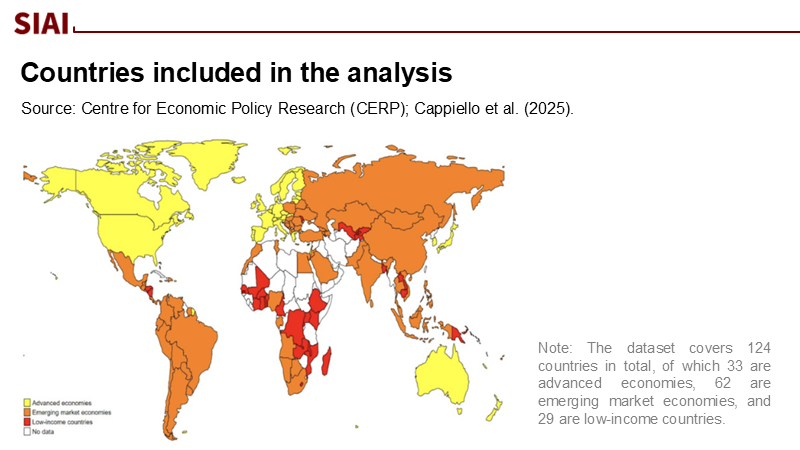

Beyond Borders: Climate Externalities Don’t Respect Fiscal Sovereignty

A central flaw in ratings that fixate on domestic targets is that climate risk is profoundly non-sovereign. Weather anomalies and water scarcity propagate through river basins, energy markets, and trade. Drought conditions in France and northern Italy, for example, reverberate through European food systems and industrial supply chains, while Mediterranean droughts strain tourism and regional power systems. Empirical evidence underscores that Europe is highly exposed to drought risks outside its borders via imported agricultural inputs, with a substantial share of EU agrarian imports projected to come from high-drought-vulnerable regions by mid-century. Add to this the lived reality: 2025 brought renewed Rhine navigation constraints that echoed Europe’s 2022 bottlenecks; prolonged Mediterranean drought has forced rationing and desalination investment. Sovereign ratings that fail to account for these cross-border transmission channels effectively treat climate risk as if it were a domestic policy variable—rather than as an integrated, regional shock to income, prices, and debt trajectories. Methodologically, this is solvable: agencies can incorporate cross-border hazard indices and trade-weighted climate exposure into their sovereign scorecards.

Diagnosing the Methodology Gap: Transparency Is Up, Integration Is Not

Regulators have pushed agencies toward more transparent disclosure on how climate is embedded in methodologies. ESMA’s 2024 consultation and subsequent final report proposed amendments to the EU’s CRA framework to improve the traceability of ESG factors in ratings. Major agencies have published cross-sector ESG frameworks, and some have acquired climate-data firms. Still, the signal in rating actions remains muted. The academic literature, by contrast, reveals robust channels from temperature anomalies to sovereign credit outcomes, and central banks now warn that extreme weather could reduce euro-area GDP by several percentage points in the coming years. The mismatch between disclosure narratives and rating elasticities is the problem. The fix is not more prose, but the adoption of new methodologies and data standards, along with explicit, auditable, climate-adjusted sovereign risk factors that link outcomes to notches.

A Direction for Reform: Measure What Matters, Where It Actually Bites

A practical path forward blends four upgrades that are implementable now. First, Outcome-Adjusted Physical Risk: replace promise-heavy inputs with observed hazard metrics—multi-year drought indices, heat-day exceedances, flood return periods—mapped to sectoral gross value added and tax bases. Europe’s water-scarcity exposures and documented disaster losses provide tractable calibrations. When surface-water scarcity threatens a share of output, that exposure should translate into a default-probability adjustment that is visible in the sovereign scorecard, with explicit assumptions and confidence intervals. Second, Realized Transition Capacity: use measured emissions intensity, verifiable decarbonization in power generation, and executed adaptation capex as positive factors, rather than weighting declared targets. Third, Networked Spillovers: adopt time-varying VAR or similar tools to model cross-country transmission in sovereign risk premia. Studies of climate policy uncertainty and sovereign CDS spillovers in the G20 offer a ready blueprint, indicating that climate policy shocks propagate through financial links. Fourth, Water and Logistics Criticality: Embed river-level and port-throughput sensitivities directly into macro scenarios for water-intensive and trade-heavy economies; recent Rhine disruptions demonstrate why a logistics-adjusted macro path should inform ratings. Each pillar produces numbers, not narratives, and collectively they shift weight from intent to impact.

Transparent Estimation: A Simple Template (and What We’d Learn)

Consider a stylized estimation for a drought-prone, export-oriented sovereign. Start with an official exposure share: suppose surface-water scarcity places x% of domestic output at risk. Apply sectoral elasticities from climate-impact assessments to translate that exposure into a one- to three-year GDP level effect under observed hazard frequencies. Combine with fiscal semielasticities—how revenue and primary balances respond to output—and add adaptation outlays from budget plans to obtain a net debt-to-GDP trajectory relative to baseline. Historical ratings data suggest that multi-percentage-point rises in debt burdens, when combined with weaker medium-term growth, are associated with negative outlooks or one-notch downgrades for similarly placed peers. Climate research modeling ratings under warming scenarios support the direction and magnitude of such adjustments. Finally, introduce a network term: estimate how climate policy uncertainty shocks in systemic partners move the sovereign’s CDS via a TVP-VAR calibrated on recent data. The result is a climate-adjusted “shadow rating” that is explicitly driven by realized hazards and verifiable mitigation—precisely what markets and ministries need.

Anticipating Objections—and Rebutting Them with Evidence

One critique argues that climate is too long-horizon to be captured by sovereign ratings, which are meant to price 5- to 10-year default risk. The counterpoint is empirical: billion-dollar disasters are occurring at record cadence now; Rhine shipping constraints have recurred within months; and Europe’s 2024 heat signals a regime shift rather than a transient spike. Another critique says methodologies lack data consistency across countries. Yet, regulators are already pushing for documented integration; Copernicus, Eurostat, and global agencies have created standardized hazard datasets, and agencies themselves have acquired climate analytics providers. A final objection holds that rewarding targets is necessary to create incentives. Fine—but it is insufficient. The evidence indicates partial and modest climate elasticities in current ratings, despite central bank warnings of material macroeconomic effects. Incentives should be attached to execution, including realized emissions intensity reductions, completed adaptation projects that demonstrably lower loss given disaster, and policies that harden critical water and logistics infrastructure. That is where default probabilities move.

Implementation Today: What Educators, Administrators, and Policymakers Can Do

Universities and policy schools should prioritize training in climate-financial analytics—encompassing time-series methods for spillovers, spatial hazard mapping, and public-finance semi-elasticities—so that rating debates are evidence-led, not slogan-led. Public administrators can publish standardized “climate fiscal risk statements” that quantify how hazard frequencies change revenue, spending, and debt over five-year horizons, with sensitivity to water and logistics; this makes it easier for agencies to adopt outcome-based factors. Ministries of finance can mandate that publicly financed adaptation projects—such as drought-resilient irrigation, river-basin management, port dredging, and grid reinforcement—report against rating-relevant KPIs, creating a direct link between capital expenditures (capex) and sovereign risk. Finally, European and international regulators should align CRA disclosure requirements with recent ESMA proposals, insisting on auditable mappings from observed climate outcomes to rating notches, and backing research that extends CDS-spillover models to climate policy channels. These steps would help move ratings from retrospective summaries of intent to forward-looking assessments of resilience.

Make Ratings Count What Counts

The climate system does not respond to national commitments; it reacts to the laws of atmospheric physics and the policies implemented. Europe's record-breaking heat in 2024, the ongoing costs from drought, and the disruptions in Rhine navigation highlight a reality that rating agencies must acknowledge: climate-related shocks are present, significant, and interconnected across countries, industries, and financial plans. Agencies have made progress in acknowledging physical risks and, since the Paris Agreement, in incentivizing ambitious goals and decreasing emissions intensity. However, the accumulation of evidence—and the real macroeconomic situation—now necessitates a clear shift towards outcome-focused and spillover-conscious approaches. Assess actual hazards and measurable mitigation efforts. Identify water and logistics challenges within macroeconomic frameworks. Simulate financial contagion resulting from uncertainty surrounding climate policy, not just local weather events. Then allow those figures to convey the message. If ratings continue to favor promises over proven resilience, capital will be directed towards vulnerability rather than adaptation—exactly the contrary of what stability requires. The solution is attainable; the time to establish standards is now.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Aggarwal, R., et al. (2024). Accounting for Climate Risks in Costing the Sustainable Development Goals (IMF Working Paper WP/24/049). International Monetary Fund.

Cappiello, L., Ferrucci, G., Maddaloni, A., & Veggente, V. (2025). Creditworthy: Do Climate Change Risks Matter for Sovereign Credit Ratings? ECB Working Paper No. 3042. European Central Bank.

Cappiello, L., Ferrucci, G., Maddaloni, A., & Veggente, V. (2025). From words to deeds: Incorporating climate risks into sovereign credit ratings. VoxEU/CEPR; also ECB Research Bulletin (July 30, 2025).

Copernicus Climate Change Service & WMO. (2025). European State of the Climate 2024 (Report & Press Resources).

EEA (European Environment Agency). (2025). Climate change impacts, risks and adaptation in Europe (EUCRA overview).

ESMA (European Securities and Markets Authority). (2024). Consultation and Final Report on amendments to CRA Regulation for ESG integration.

Global Carbon Project. (2024). Fossil fuel CO₂ emissions increase again in 2024 (Global Carbon Budget update).

IEEFA (Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis). (2025, March 19). Climate risks underplayed in recent credit rating actions.

Klusak, P., Agarwala, M., Burke, M., Kraemer, M., & Mohaddes, K. (2023). Rising Temperatures, Falling Ratings: The Effect of Climate Change on Sovereign Creditworthiness. Management Science, 69(12), 7468–7491.

Moody’s Ratings. (2022). Sovereigns—Rating Methodology (and cross-sector ESG framework).

Naifar, N. (2024). Spillover among Sovereign Credit Risk and the Role of Climate Uncertainty. Finance Research Letters, 61, 104935.

NOAA National Centers for Environmental Information. (2025). U.S. Billion-Dollar Weather and Climate Disasters (2024 overview).

Reuters. (2025, June 30 & July 17). Low water levels hamper shipping in Germany’s Rhine River.

World Bank. (2024, May 15). Europe urgently needs to increase its disaster and climate resilience (press release; 2023 losses and GDP risk).

Comment