Exit the Empire, Enter the Network: Why Friendship—not Force—Secures China's Lifelines through Malacca and the Pacific

Input

Modified

This article was independently developed by The Economy editorial team and draws on original analysis published by East Asia Forum. The content has been substantially rewritten, expanded, and reframed for broader context and relevance. All views expressed are solely those of the author and do not represent the official position of East Asia Forum or its contributors.

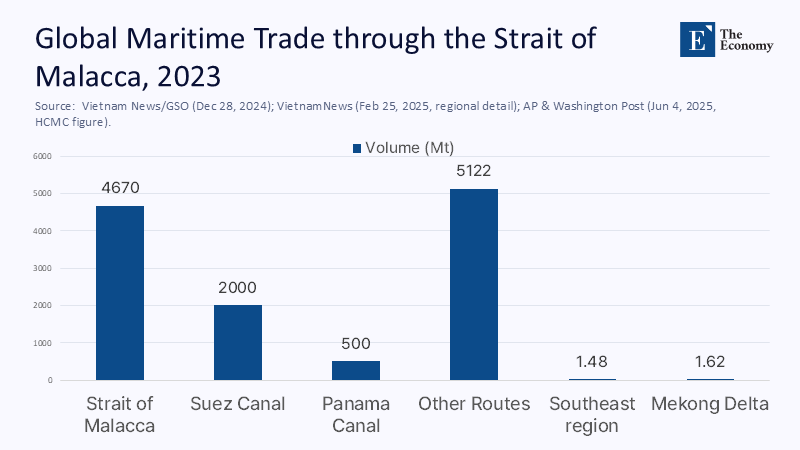

The figure that determines the discussion is 38. In 2023, thirty-eight percent of all global maritime commerce passed through the Strait of Malacca, the narrow connection between the Indian and Pacific Oceans. That's not just a figure of speech; it's a fact about the supply chain. In 2024, ships navigating the Straits of Malacca and Singapore reached an all-time high of 94,301 transits, while nearly 80 percent of China's oil imports still arrived home through the South China Sea and the Malacca chokepoint. Simultaneously, geopolitical shifts elsewhere caused a significant increase in freight rates, and insurance providers began reassessing risk premiums concerning disputed waters. The Strait is crowded, limited, and crucial. China can attempt to enforce its security, or it can structure its approach for resilience. Only one of these choices lowers the total costs associated with chokepoints, hedging coalitions, and sporadic crises. The other option increases those costs—sometimes significantly—by instigating counterbalancing efforts and pricing in a "coercion premium" for every journey. The strategic calculus is not idealistic; it is simply more economical and safer to have allies.

From Authority to Access: Reframing the Choice

The conventional frame often pits sovereignty and deterrence against accommodation. However, in Southeast Asia, the fundamental policy trade-off is not between toughness and softness; it is between authority and access. Access, in this context, means reliable passage through the Malacca, Singapore, Luzon, and Taiwan Straits, and predictable docking, bunkering, and transshipment at ASEAN ports when global networks are already strained. The focus should shift from projecting authority through Coast Guard intimidation or unilateral administrative orders, which may win a headline but tend to lose when the littoral states respond with hedging, enhanced maritime domain awareness, and new defense pacts. The result is not 'stability through strength' but 'friction through resistance.' The better reframing is: what portfolio of policies maximizes China's expected access under stress conditions? In a world where Red Sea rerouting already doubled some container rates in mid-2024, the need for reliable access is more pressing than ever. The only scalable answer is coalition building with the states that physically host the sea lanes China needs most.

The Numbers in the Narrows

Begin with the tonnage. UNCTAD estimates global maritime trade at 12,292 million tons in 2023. If 38 percent transited Malacca, roughly 4,670 million tons traversed that strait—about 12.8 million tons per day. In shipping terms, Malacca and Singapore have become the indispensable middle mile of Asian trade, with ship transits setting new records in 2024. This is not a route China can unilaterally police without compounding risks: portions of the straits are inside Indonesian and Malaysian waters, and Singapore and regional partners coordinate the traffic separation scheme. The administrative reality of shared jurisdiction and joint safety mechanisms means that "being an emperor to SEA countries" cannot control the corridor without their consent. It can, however, trigger costly responses that congest or politicize access. The geography is fixed; the incentives are not.

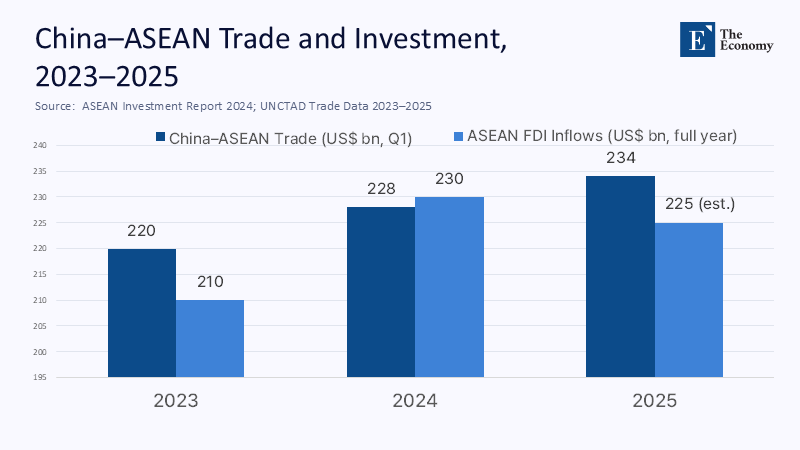

The economic interdependence between China and ASEAN is a compelling argument for a 'friendship-first' approach. ASEAN is China's largest trading partner, as seen in recent years; in Q1 2025, bilateral trade totaled about US$234 billion. China also channels the bulk of its seaborne energy through Malacca, with nearly four-fifths of oil imports historically transiting the South China Sea and the strait. Meanwhile, ASEAN's FDI inflows hit a record US$230 billion in 2023, with green- and digital-economy projects surging—opportunities China wants to anchor in supply-chain partnerships rather than watch move to rivals. Add RCEP's consolidation effects, and you have an economic case for 'friendship first' that is not moralizing; it is portfolio management. A region that owns the doors to your lifelines is a region you over-invest in diplomatically, commercially, and logistically.

The Coercion Premium

Coercive tactics in the South China Sea—blocking runs, water cannoning, unsafe intercepts—do not create predictable access; they create pricing events. Underwriters review war-risk maps, shippers add buffer time and fuel, carriers bunch at transshipment hubs, and a hidden tax appears on every movement. In 2024, amid multiple maritime disruptions, the Shanghai Containerized Freight Index more than doubled over late-2023 levels; rerouting around the Cape added up to 12 days on Asia–Europe voyages and drove measurable lifts in vessel demand. Insurers publicly warned that premium surcharges can jump by 20 percent or more when a region is reclassified as higher risk—even modest changes in classification for waters around key shoals compound across thousands of sailings. The bill does not come due in a press conference; it arrives via rate sheets, charter talks, and balance-of-year guidance.

The tactical picture is no better. 2024–2025 saw repeated clashes around Second Thomas and Scarborough Shoals. Manila documented close-approach maneuvers within 50 meters of its outpost; videos of water cannon attacks circulated widely; and Australia and the Philippines deepened defense cooperation, alongside new trilateral and minilateral exercises. The legal baseline remains the 2016 arbitral ruling, which undercuts expansive maritime claims under UNCLOS. Suppose the operational signature of Chinese policy remains regulation-backed assertiveness at sea. In that case, the strategic consequence will be faster balancing, more exercises, more basing access for external navies, and tighter interoperability in the very corridors China needs to keep de-risked. That is the coercion premium: not just higher insurance and freight, but thicker, more capable coalitions at the choke points, posing significant strategic risks.

ASEAN Is Not One Country: Targeted Friendship as a Force Multiplier

Treating ASEAN as a single counterpart is a category error. The bloc is a mosaic of incentives. Thailand's 2024 tourism recovery was led by 6.7 million Chinese visitors, roughly a fifth of total arrivals, after visa facilitation—proof that calibrated, mutually respectful policy choices unlock tangible goodwill with macro spillovers in services, aviation, and retail. Indonesia's nickel revolution, accelerated since the 2020 ore-export ban, now shapes global EV supply chains; Chinese-backed processing dominates large segments of value-added output. Vietnam's export engine, driven by China-plus-one strategies, hit new records in 2024 and deepened positional value as a manufacturing and logistics partner. These are not soft-power anecdotes; they are industrial and consumer-market channels that, when nurtured, become informal insurance policies for keeping straits open and politics calm when crises elsewhere tighten capacity, emphasizing the importance of mutual respect in policy choices.

The multiplier works the other way, too. When ASEAN governments perceive pressure, they hedge with trade remedies against overcapacity, deeper ties to outside security partners, or slow-walking of connectivity projects. Persistent coercion around contested features hardens domestic politics in Manila and Hanoi and narrows maneuvering space in Kuala Lumpur and Jakarta. The result is not just reputational damage but policy lock-in: defense pacts, interoperability exercises, and risk-averse shipping practices that are difficult to unwind. In a low-elasticity chokepoint like Malacca, where around 94,000 ship transits per year leave little room for error, friction costs compound fast. Under stress, every stakeholder defaults to the rules, procedures, and coalitions they trust. Friendship expands those circles. Pressure shrinks them.

Law, Procedure, and the Politics of Passage

The region already owns a usable architecture for predictable access. The Co-operative Mechanism for the Straits of Malacca and Singapore, stewarded by the littoral states and user states, underwrites navigation safety and aids-to-navigation financing—the ASEAN Outlook on the Indo-Pacific centers on inclusive, rules-based cooperation over rivalry. Code-of-Conduct talks, however halting, preserve a channel for de-escalation and technical standard-setting. A friendship-first strategy would double down on these procedural anchors, not bypass them. That means more transparent funding into navigation safety and environmental projects in the straits; support for ReCAAP-aligned information sharing; and a visible, consistent de-escalation protocol for encounters near sensitive features, including graduated "stand-off distances" and third-party verification mechanisms acceptable to ASEAN coast guards. Procedure is not a concession. In crowded waters, it is the price of passage.

Equally, Chinese domestic legal moves that widen coast-guard enforcement discretion at sea may be read regionally as unilateralism cloaked in administrative law. The 2021 Coast Guard Law and the 2024 Order No. 3 on enforcement procedures alarmed neighbors and outside powers because they could normalize aggressive behaviors in undefined "jurisdictional waters." Rescinding or clarifying these measures' application in contested zones, or formally carving out AOIP-aligned protocols, would support the narrative that Beijing chooses option #1—befriending ASEAN—not merely in speeches but in operational practice. The dividends would arrive via lower risk premia, steadier schedules, and a reduced appetite among ASEAN states to invite extra-regional navies to thicken presence in the very straits China depends on.

A Playbook for the Friendship Option

Friendship can be engineered. Start with "unsexy" fixes that matter to mariners: fund additional aids to navigation, vessel traffic services, and hydrographic surveys across the Straits of Malacca and Singapore; expand training slots and equipment grants for ASEAN coast guards that commit to shared de-escalation protocols; and co-sponsor ReCAAP-compatible reporting upgrades. These are visible signs of good faith to the littoral states that manage the corridor daily, and they reduce incidents that drive up insurance costs. They also make it harder for critics to claim China free-rides on public goods while demanding deference. Make the proof cumulative and boring—a dozen small operational wins that lower collision, delay, and boarding risks. In the arithmetic of access, fewer incidents mean fewer excuses for outside "fly-ins" and fewer reasons for rating agencies and underwriters to shade premia upward.

Then scale the policy stack. Lock in the upgraded ASEAN-China FTA 3.0 and plumb it into RCEP rules on digital and green trade to stabilize expectations on customs, data, and standards. Use targeted, rules-based finance to complete last-mile linkages from ASEAN industrial parks to deep-water ports—especially where logistics bottlenecks push shippers toward alternative hubs. Pilot green shipping corridors with Singapore and Port Klang to align with EU ETS-driven cost structures and demonstrate shared climate-logistics leadership. In tourism and services, keep permanent, reciprocal visa facilitation with major ASEAN markets and hard-target safety cooperation to restore Chinese traveler confidence. Finally, formalize a public yardstick: measure success not by patrol counts but by reductions in incident rates, average transit times through the straits, and the spread between Malacca-exposed and non-exposed shipping insurance premia. Access is what gets measured and improved.

Anticipating the Counter-Arguments

One critique says coercion deters opportunism: if Manila or Hanoi believes Beijing will escalate, they will think twice before "provocations." The recent record suggests the opposite. High-risk maneuvers have coincided with tighter Philippines-Australia ties, broader minilateral drills, and more cameras on deck. Rather than deterring, blunt force has accelerated balancing, invited more outsiders into ASEAN waters, and hardened domestic politics against compromise. Another critique asserts that "friends are fickle," and only hard power guarantees passage. But the straits are administered, not conquered; Indonesia, Malaysia, and Singapore have their own electorates, bureaucracies, and legal regimes. A force-first posture cannot rewrite that. A procedure-first posture, funded and patient, can embed China as a dependable co-manager of safety and capacity, while leaving sovereignty untouched. In a finite channel handling ~30–38 percent of global seaborne trade, depending on the measure, reliability comes from routines agreed with the people who operate the lights and lanes, not from the tail-races of water cannons.

A final critique warns that friendliness will be read as weakness. The answer is to tie de-escalation to clearly articulated red lines and to public metrics. If incidents fall, premiums drop, and transits speed up, you are buying strategic depth with cash-flow savings. If a counterpart tests the system, pause privileges, conditional financing, or corridor projects. The posture is not concessionary; it is transactional and enforceable. It also aligns with ASEAN's own declared preferences for openness, inclusivity, and rules-based cooperation. Put differently: friendship in Southeast Asia is not ideology. It is infrastructure. You either build it or you pay for its absence at scale.

The Cost Curve Bends Toward Friendship

Return to Figure 38. With over a third of global maritime trade passing through the Malacca Strait, the rarest commodity is not ship capacity or hulls but rather predictability. China's oil and goods traverse these routes, along with its diplomatic and reputational stakes. Coercive actions in nearby waters have yielded few lasting benefits while increasing expenses due to insurance premiums, delays from rerouting, and hastened external balancing. In contrast, intentionally shifting to a "friendship first" approach—investing in safety and navigational public resources, establishing de-escalation agreements, completing market-opening regulations, and seeking incremental victories in tourism, minerals, and manufacturing—reduces risk in the crucial routes: from Malacca to Singapore, and through the South China Sea, Luzon, and the Taiwan Straits into the Pacific. The key question is no longer whether China can assert its dominance at sea, but whether it can gain consent on land. Should it succeed, its maritime operations will proceed more swiftly, economically, and safely. If it fails, the cost associated with each passage—financially, politically, and strategically—will continue to increase. In congested waterways, empires become stagnant; networks advance.

The original article was authored by Ian Seow Cheng Wei, a graduate of the University of Oxford’s Master of Philosophy in International Relations Programme. The English version, titled "China's security success conditional on Southeast Asia," was published by East Asia Forum.

References

AP News. (2025, August 22). The Philippines condemns China's swarm of forces near disputed shoal.

Asia Society Policy Institute. (2025, February 17). ASEAN caught between China's export surge and global de-risking.

ASEAN Secretariat. (2024, June 12). Overview of the ASEAN–China Comprehensive Strategic Partnership.

EIA (U.S. Energy Information Administration). (2024–2025). World Oil Transit Chokepoints; South China Sea.

Informare (Port Economics Journal). (2025, January 9). New annual record for the transit of ships in the Straits of Malacca and Singapore.

ISEAS–Yusof Ishak Institute. (2024). Advancing the ASEAN Outlook on the Indo-Pacific beyond principles.

Jamestown Foundation. (2024, June 21). New China Coast Guard Regulation buttresses PRC aggression in the South China Sea.

Permanent Court of Arbitration. (2016, July 12). South China Sea Arbitration (Award).

Reuters. (2025, August 22). Philippines, Australia to seal new defence pact as China tensions rise.

Reuters. (2025, January 17). Thai PM to reassure Chinese tourists on security; 6.7 million Chinese visitors in 2024.

UNCTAD & ASEAN Secretariat. (2024, October 9). ASEAN Investment Report 2024.

WEF (World Economic Forum). (2024, February 15). These are the world's most vital waterways for global trade.

Wilson Center. (2024, February 13). 360° view of policies needed to secure shipping chokepoints.

Comment