Pricing Dependence: Turning Retaliatory Protection into Rules for the Age of Scale Subsidies

Input

Modified

This article is based on ideas originally published by VoxEU – Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR) and has been independently rewritten and extended by The Economy editorial team. While inspired by the original analysis, the content presented here reflects a broader interpretation and additional commentary. The views expressed do not necessarily represent those of VoxEU or CEPR.

Retaliation will continue as long as the cost of dependence is not addressed. Tariffs such as five-year duties and one-hundred-percent taxes are indications of a more profound issue: the externalities stemming from scale subsidies that create concentrated capacity within key supply chains. The statistics that support this argument—dominant positions in batteries and solar, a significant share of EV exports—should not be seen as moral evaluations; instead, they serve as indicators of risk. The solution involves front-loading the analysis. Before granting subsidies, require accurate assessments of capacity impact, impose a dependence cost when projected exports risk exceeding agreed limits for partners, and provide predictable, reciprocal access once transparency and openness are confirmed. This should be enacted in a plurilateral context that aligns with WTO regulations and employs interim appeal arbitration to maintain the credibility of adjudication. In this way, retaliation becomes a last resort rather than the default position. The aim is to preserve the advantages of scale and learning while eliminating the single point of failure that currently influences political dynamics. By pricing the dependence, the overall argument becomes less volatile and more manageable. In 2024, the European Union moved from provisional to definitive countervailing duties on Chinese battery-electric vehicles and locked them in for five years. Weeks earlier, the United States lifted tariffs on Chinese electric cars to 100% and on solar cells to 50%. These steps landed in a market where China supplied 40% of the world’s electric-car exports in 2024, produced about 80% of global battery cells, and dominated more than 80% of the solar manufacturing chain. Prices echoed the imbalance: global solar-module spot prices fell by roughly half in 2023 as capacity ramped faster than demand, while battery manufacturing announcements for 2025 alone would exceed projected demand by a factor of two to five. The result is a new kind of risk premium baked into trade politics. Policymakers are no longer reacting only to alleged “cheating.” They are responding to the systemic exposure that comes from sourcing critical technologies from a single dominant supplier—and they are building multi-year defenses to reduce that exposure.

Reframing the Argument: From Cheating to Systemic Dependence

The familiar story treats subsidies as “cheating” that invites punishment. That moral lens misses the operational logic now driving policy. Retaliatory protection today is a response to perceived system risk. When state support produces concentrated capacity in upstream bottlenecks—cathodes, anodes, cells, wafers—importers infer not just an injury to their producers but a vulnerability in their infrastructure and climate programs should a single foreign source falter or weaponize access. The European Union’s move to definitive duties on Chinese EVs and the United States’ escalation on EVs and solar were designed to buy time, curb dependence growth, and force diversification, not to end clean-tech trade. The same logic helps explain why, with the WTO Appellate Body still paralyzed, governments are turning to semi-automatic instruments—countervailing duties, anti-dumping, local-content rules—and to the MPIA to keep disputes legally justiciable among willing members. Seen this way, the puzzle is not why retaliation happens, but why it is calibrated to last for years: the hazard being managed is dependence, and dependence takes time to unwind.

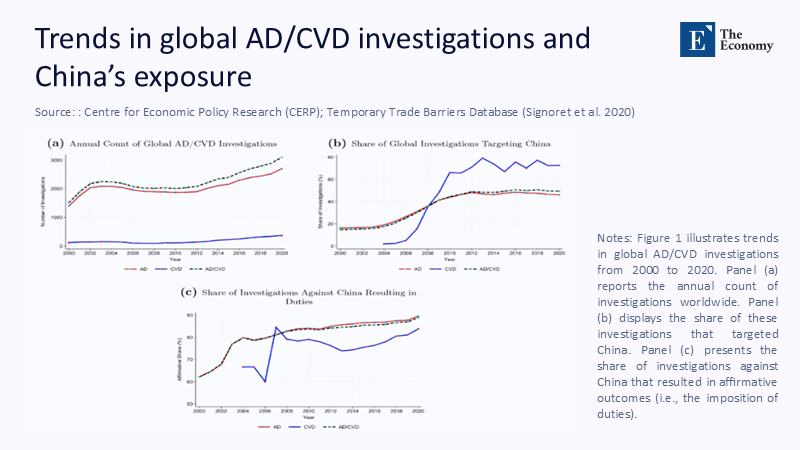

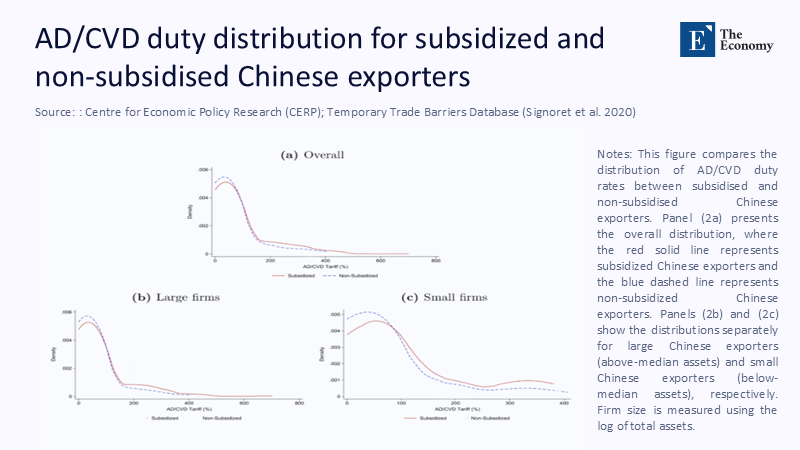

The Evidence Base: Concentration, Overshoot, and the Retaliatory Response

Concentration is no longer contested. The IEA reports that China produced roughly 80% of battery cells in 2024 and controls nearly all anode and most cathode active-material capacity; in solar PV, it exceeds 80% across manufacturing stages. BloombergNEF tracks lithium-ion cell capacity announcements that by end-2025 will far outstrip demand, a shift mirrored by a 50% collapse in module spot prices in 2023. Trade policy has reacted in kind. The EU adopted definitive countervailing duties on Chinese EVs effective October 2024, while the United States finalized Section 301 increases on EVs and solar inputs. The WTO recorded a renewed upswing in countervailing initiations in the first half of 2024. Behind these remedies lies a micro-evidence base: at the product level, Chinese subsidies raise exports and curb imports, with upstream support magnifying downstream surges; at the firm level, retaliatory tariffs wipe out roughly a quarter of the revenue growth that subsidies would otherwise generate. In the WTO’s own monitoring, countervailing initiations peaked at 56 in 2020, eased thereafter, and then rebounded to 35 in the first half of 2024 alone, foreshadowing more measures as cases conclude—a tempo aligned with the policy shift toward defensive, multi-year instruments.

Mechanism, Not Morality: How Scale Subsidies Trigger Retaliation

The mechanics of retaliation are more technical than moralistic. Scale subsidies lower the cost of capital and inputs, accelerate learning curves, and lock in supplier power. When capacity overshoots domestic demand, utilization requires exports; prices fall toward subsidized average costs and trigger injury thresholds embedded in anti-dumping and countervailing-duty law. What turns routine trade friction into a multi-year defense is the dependence channel. Dominant shares of batteries, anodes, cathodes, and wafers mean that a policy shock, export restriction, or logistics disruption in one jurisdiction can derail another’s transport, power, or industrial decarbonization plans. Policymakers then reach for tools that work even while the WTO’s top appeals body remains frozen: national remedies, local-content measures, and MPIA arbitration among participants. The concentration trend is not ebbing on its own. In 2024, three producers accounted for an average of 86% share across key critical minerals supply chains. By 2024, China will still draw roughly three-quarters of global clean-tech factory investment, consolidating upstream advantages. The incentives, in short, make retaliation a risk-management response.

A New Policy Lens—and How to Implement It

If dependence is the hazard, price it explicitly at the point of subsidy rather than back-solving with blunt tariffs. A Dependence-Adjusted Subsidy Test would require any large, export-exposed package in batteries, EVs, PV, or critical inputs to clear two quantified hurdles. First, a Global Capacity Impact Assessment would publish modeled post-subsidy market shares by supply-chain stage, capacity-to-demand ratios, and an import-dependence index for major partners, with ranges and data sources disclosed. Second, a Dependence Price would attach a refundable charge to the subsidy if modeled exports push any partner’s index above an agreed threshold—think an escrow that funds diversification or grid integration in recipient markets until dependence recedes. To allocate scarce access predictably, a reciprocity auction would link tariff-rate quotas or mutual-recognition benefits to verified transparency and openness in the exporting firm’s home market. None of this requires waiting for a full WTO appellate revival. A critical-tech plurilateral could adopt standard templates, publish annual dashboards, and refer disputes to the MPIA among consenting members, restoring legal predictability while the broader system remains stalled. The UK’s 2025 decision to join the MPIA, alongside the EU and others, shows such arrangements can scale.

Concretely, thresholds could be set so that if modeled post-subsidy global shares exceed, for any single country, 70–80% at a key stage, or if capacity-to-demand ratios rise above, say, 1.4 for two consecutive years, the dependence charge activates automatically. The charge would taper as diversification materializes and would sunset when measured shares fall back inside the band. Because the assessment, the trigger, and the taper are published ex ante, firms and governments can plan investments with more straightforward risk pricing, and trading partners can calibrate their own responses without resorting to ad hoc, open-ended duties. Governance would matter: independent auditors could verify inputs and modeling, and results would be notified under the WTO’s subsidies rules with standardized templates. Least-developed countries could receive temporary exemptions and technical assistance to publish their own dashboards. Climate-critical projects would qualify for lower charges if they demonstrably reduce global concentration—say, by siting new capacity where shares are smallest or by licensing technology across regions.

Implications for Educators, Administrators, and Policymakers

Education systems should teach capacity risk the way they teach financial risk. Economics and policy programs can require students to build simple capacity-demand models that integrate announced factory pipelines, learning rates, and trade-remedy exposure, then translate those metrics into procurement, competition, and climate-policy choices. Business schools can train managers to treat supplier concentration as a measurable externality when assessing partnerships and overseas siting. Administrators in industrial-policy agencies and development banks can embed dependence dashboards into project appraisal, with disbursements linked to diversification milestones, local content that genuinely widens the supplier base, and contingency clauses that redirect support if modeled dependence breaches thresholds. Procurement authorities can incorporate resilience scores into award criteria, favoring bids that pair low prices with credible multi-sourcing or regional assembly.

For universities and think tanks, the research agenda is equally practical: publish open, replicable capacity trackers that merge customs data, announced factory pipelines, and policy changes; develop dependence indices that distinguish benign specialization from brittle concentration; and test how procurement scoring rules shift supplier behavior. Public-sector training can go further, equipping case handlers in trade-remedy authorities to read capacity dashboards alongside injury metrics so that remedies become a bridge to diversification strategies rather than an end in themselves. Cross-border degree programs and executive courses can pair data labs with live policy simulations—an EU-U.S. team running a capacity impact assessment on a proposed cathode plant; an ASEAN-Africa cohort designing reciprocity auctions for PV modules—so the next generation can operationalize resilience rather than merely debate it.

Anticipating the Counterarguments—and Rebutting Them

Two critiques deserve answers. First, that cheap Chinese clean-tech exports are an emissions gift the world should not refuse. The climate arithmetic matters: in 2024, China exported a vast volume of clean-energy goods, and lower prices plausibly accelerated deployment abroad. But climate ambition does not require structural concentration. With battery and PV capacity already exceeding near-term demand and critical minerals processing highly concentrated, diversification can proceed without slowing installations. Indeed, credible diversification reduces the risk that a single disruption stalls whole decarbonization programs. Second, that retaliation is mere protectionism, while others subsidize too. It is true that industrial subsidies globally are at their highest level since the financial crisis, and that the stock of trade restrictions has risen. The answer is not unilateral restraint by a few, but symmetrical discipline for all: transparent capacity assessments, a dependence price that travels with the subsidy, and predictable access rules under a plurilateral umbrella. That path keeps markets open to low prices while shrinking the system-level exposure that provokes the longest and most sweeping remedies.

Retaliation is a Symptom; Dependence is the Disease

Retaliation will persist as long as the issue of dependence is not tackled. Tariffs such as five-year duties and one-hundred-percent taxes are signs of a deeper problem: the externalities arising from scale subsidies that create concentrated capacity within essential supply chains. The data supporting this claim—dominant roles in batteries and solar, a substantial portion of EV exports—should not be interpreted as moral judgments; instead, they function as indicators of risk. The solution involves prioritizing the analysis. Before providing subsidies, it is essential to require precise evaluations of capacity impacts, impose a dependence cost when anticipated exports threaten to surpass agreed limits for partners, and ensure predictable, reciprocal access once transparency and openness are established. This should be implemented in a plurilateral framework that complies with WTO regulations and utilizes interim appeal arbitration to uphold the credibility of adjudication. In this manner, retaliation can be viewed as a last resort rather than an initial response. The objective is to maintain the benefits of scale and learning while eliminating the single point of failure that currently affects political dynamics. By pricing the dependence, the overall argument becomes less unstable and easier to manage.

The original article was authored by Yusheng Feng, an Econ Ph.D. student at the University of Hong Kong, along with three co-authors. The English version, titled "Industrial policy and retaliatory protection under the WTO: Lessons from China," was published by CEPR on VoxEU.

References

AP News. (2024). The EU is imposing duties on electric vehicles from China after trade talks fail.

BloombergNEF. (2024, April 12). China already makes as many batteries as the entire world wants.

BloombergNEF. (2025, April 28). China dominates clean technology manufacturing investment as tariffs begin to reshape trade flows.

Borderlex. (2025, July 16). Analysis: Could MPIA become new default WTO appeals system?

Carbon Brief. (2025, July 22). China’s 2024 clean-energy exports will cut overseas CO₂.

CEPR VoxEU. (2025, August 22). Industrial policy and retaliatory protection under the WTO: Lessons from China.

European Commission. (2024, December 12). Definitive countervailing duties on imports of BEVs from China.

IEA. (2024). Solar PV global supply chains: Executive summary.

IEA. (2024–2025). Global EV Outlook—Executive summary; Electric-vehicle batteries; Trends.

IMF. (2024, August 23). Trade Implications of China’s Subsidies (Working Paper 2024/180).

International Affairs Australia – Australian Outlook. (2024, October 21). “It’s you, not me”: China’s subsidies and global trade tensions.

OECD. (2025, June 23). The state of play of industrial subsidies as of 2023.

Office of the United States Trade Representative. (2024, September 12). Section 301 tariff modifications determination.

WTO. (2024, November 20). Trade Monitoring Report, mid-Oct 2023 to mid-Oct 2024.

WTO Trade Remedies Data Portal. (2025). Countervailing investigations and measures.

Comment