Make Scale Cheap Again: Recalibrating EU Merger Control to Unlock Productivity—While Keeping Big Tech in Check

Input

Modified

This article is based on ideas originally published by VoxEU – Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR) and has been independently rewritten and extended by The Economy editorial team. While inspired by the original analysis, the content presented here reflects a broader interpretation and additional commentary. The views expressed do not necessarily represent those of VoxEU or CEPR.

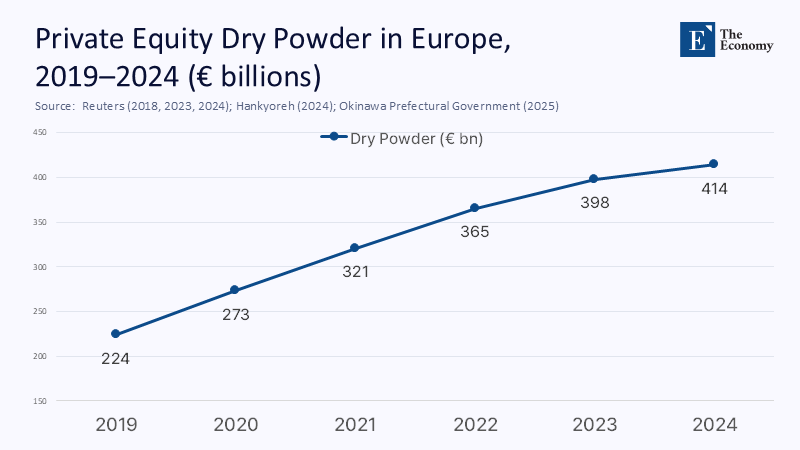

Europe experienced a slight 0.4% increase in labor productivity per hour in 2024, following a decline of 0.6% in the previous year. In contrast, U.S. hourly productivity has risen by 6.7% since the end of 2019, while the euro area has seen only a 0.9% increase. The disparity is not merely a source of embarrassment; it is becoming exacerbated. In a continent facing an aging workforce that must maximize output with limited resources, these fractional changes significantly impact wage growth, export competitiveness, and fiscal flexibility. Meanwhile, private markets boast unprecedented financial strength, with €414 billion in European dry powder available in 2024—much of it specifically allocated for acquiring underperforming assets and improving them. However, transactions that would enable a shift in control from less efficient owners to more capable ones often face slow approval processes that can stretch on for months or even years, particularly when the deals become “complex.” Consequently, there is a subtle hindrance to reallocation: potential productivity improvements are postponed, sometimes indefinitely, not due to a lack of efficient scale but because the process of achieving it is excessively slow and uncertain.

From “European Champions” vs. “Market Power” to the Real Scarcity: Time

The debate over merger control in Europe often contrasts two extremes: loosening rules to create “European champions” or tightening them to prevent concentration. However, the real issue is not a lack of capital or ideas, but the time needed to deploy them effectively. When a capable owner can enhance productivity in a target company, the key question becomes how quickly the benefits can materialize and under what conditions.

In 2024, the European Commission reviewed 392 notifications and made 398 merger decisions, rarely prohibiting any. Most cases cleared in Phase I, but deeper scrutiny led to significant delays; EU Phase II reviews averaged over a year, with pre-notification extending timelines further. The real chilling effect is seen in the withdrawal of deals and the uncertainty that affects investment, hindering the deployment of the €414 billion capital that remains idle.

What the Numbers Actually Say About Europe’s Reallocation Problem

Europe's productivity issues are not just a post-pandemic anomaly. The European Central Bank highlights that while U.S. market-services productivity has surged since 2019, the euro area has seen little progress. In 2024, the EU managed a modest 0.4% productivity gain after a down year, indicating sluggish growth. Slow reallocation means small annual gains have a significant impact on living standards, especially during simultaneous energy shocks, demographic shifts, and rising capital costs.

In the deal market, European M&A values improved in 2024 despite subdued volumes; private equity rebounded, but exits and fundraising remained inconsistent. The region isn't lacking capital but rather conviction, as LPs seek returns and GPs need clear exit strategies. Prolonged review processes—like merger control and foreign investment checks—raise the costs of taking risks, and while Europe has substantial dry powder, investors are hesitant amid uncertainty.

Where Rigidity is a Feature, Not a Bug—and How to Keep It That Way

None of this argues for a laissez-faire pivot. The EU was right to build bespoke guardrails for gatekeepers and foreign-subsidized entrants. The Digital Markets Act forces large platforms to notify all acquisitions and obey conduct rules; while notifications currently inform rather than automatically trigger merger action, proposals now on the table would flip the burden of proof for gatekeepers, recognizing the systemic risk of serial “ecosystem” buys. Likewise, the Foreign Subsidies Regulation (FSR) adds a stand-alone notification and standstill regime for transactions meeting thresholds where non-EU state support may distort bidding. In a world of overcapacity shocks and state-backed champions, those protections are part of Europe’s defensive moat.

Two caveats matter for productivity policy. First, the Court of Justice’s September 2024 ruling reined in the Commission’s ability to assert jurisdiction over below-threshold deals via Article 22 referrals unless a member state competition authority has its own jurisdiction. This overdue legal boundary reduces the perception of “moving goalposts.” Second, the FSR’s additional 25-plus-90 working day pathway and expansive information demands have real deal-timing costs even for benign transactions; the first in-depth FSR probe in 2024 signaled Brussels’s willingness to use it. The goal is not to scrap either tool. It is to narrow their use to the genuine systemic-risk perimeter, while making everything outside that perimeter predictably fast.

Why Investors Call the System “Anti-Market,” and Why That Matters

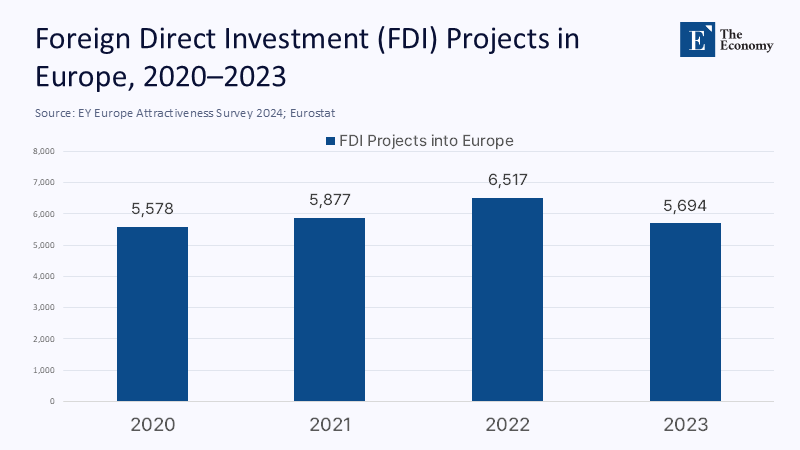

Institutional investors do not judge regimes by the rarity of prohibitions; they judge them by time-to-certainty and the odds that rules change mid-flight. Europe’s formal intervention rate is low by historic standards. Still, the combination of longer prenotification, more frequent remedies for non-horizontal theories of harm, and layering of FSR and national security screenings creates a fog that lowers bid prices or keeps bids from being made at all. Surveys and sentiment snapshots consistently surface “regulatory and geographical considerations” as barriers to cross-border investing within the EU itself. Foreign direct investment projects into Europe fell in 2023, the first decline since 2020, as executives cite policy complexity among the deterrents. These are not ideological gripes; they are underwriting inputs.

Predictability also matters politically. Europe’s outgoing competition chief recently warned against a “big is beautiful” drift and gestured toward guideline updates that emphasize innovation and resilience. The caution is warranted: bending rules for national champions would likely entrench the wrong kind of scale. But clarity that neutral, productivity-enhancing consolidation will be evaluated and cleared quickly is not a “champions” agenda—it is a growth agenda. If the prevailing brand remains “anti-market,” Europe will leave part of that €414 billion in PE capital on the runway, and more of the projects that need new owners will grind through another year under the old ones.

A Recalibration That Keeps the Moat—and Opens the Gate

We can improve the equilibrium by distinguishing between two categories:

Category A involves system-risk consolidation, such as acquisitions by gatekeepers or firms with foreign subsidies that could disrupt supply chains. This category requires complete DMA/FSR tools and strong presumptions of harm for repeat acquirers.

Category B focuses on productivity-enhancing consolidation without gatekeeper or subsidy concerns and where harm is local or temporary. This category should benefit from expedited processes and remedy-first approaches.

To change behavior quickly, three actions can be implemented:

1. Establish a “Productivity-Safe Harbour” for PE-backed and industrial acquisitions under certain thresholds, allowing a 25-working-day clearance unless the Commission identifies a specific harm by day 10.

2. Introduce a “Remedy-First” fast track for parties offering responsive divestitures, with a conditional Phase I decision within a guaranteed timeframe.

3. Publish ongoing statistics on prenotification durations and information requests by sector to enhance planning and accountability.

The aim is precise: where risks are manageable, Europe should move swiftly to seize opportunities.

The Quantitative Case for Making Scale Cheap

What would faster reallocation buy Europe? Assume that 5% of EU firms are suitable for stewardship upgrades by more efficient mid-market acquirers. If half of these deals close quicker, saving six months in ownership transfer, a conservative estimate suggests a 6–8% productivity uplift in targets over three years. This six-month acceleration could bring forward roughly one-sixth of that gain, resulting in a cumulative increase of 0.2–0.4 percentage points in EU-wide labor productivity over three years, with compounding benefits thereafter.

Two factors could enhance this impact: first, abundant target firms in market services have a high payoff for better governance and technology; second, there is ample investment capital, as indicated by record dry powder in Europe. The key variable is procedural certainty. If regulators can shorten the approval process for Category B deals without compromising scrutiny for Category A, these gains could be achieved. This estimate combines documented sectoral gaps with conservative productivity uplift assumptions and is intentionally modest and reversible based on empirical outcomes.

Guardrails for the Moat: Keeping Big Tech and Subsidies in Frame

A recalibration towards speed does not neuter Europe’s moat. Gatekeeper acquisitions still merit a higher bar; Bruegel’s proposal to empower the Commission to scrutinize any gatekeeper acquisition and invert the burden of proof is sound, as long as the defined gatekeeper remains tight and evidence-led. And the FSR should remain a live instrument against state-distorted bids—but with improved predictability. Here, refinements are practical: standardize FSR information requests, publish anonymized timelines, and explicitly prioritize cases in sectors flagged by actual subsidy probes to date, rather than casting a blanket over benign deals. The September 2024 court ruling on Article 22 should calm nerves about jurisdictional overreach; the Commission’s subsequent withdrawal of its 2021 guidance reflects that the law is settling. None of these tweaks cedes ground to predatory deep pockets; they reduce the ambient uncertainty that keeps good deals shelved.

What This Means for Classrooms, Campuses, and Ministries

For educators and university leaders, slow reallocation limits partnerships with well-capitalized companies for apprenticeships and curriculum modernization. Faster ownership transfers to operators investing in technology could enhance collaboration on micro-credentials and employability pathways. Administrators should expect more dynamic local business ecosystems, allowing course offerings to align with larger employers' needs rather than just smaller firms.

Policymakers can take action without changing treaties by piloting productivity safe harbours and remedy-first tracks under existing guidelines. Enhancing transparency with prenotification metrics and sectoral breakdowns would improve accountability. National authorities should synchronize FDI screening and merger timelines to reduce standstill issues, while member states need to address declining green-field FDI and regulatory complexities impacting cross-border investment. Failing to act risks maintaining a process that slowly hinders productivity as investors look elsewhere.

Anticipating the Counter-Arguments—and Answering Them

Critics argue that faster clearances entrench power, especially in digital ecosystems, which is a concern addressed by the DMA and gatekeeper focus. However, this issue is less relevant for Europe’s mid-cap manufacturing and services, where harm is local and remedies straightforward. Others warn that procedural speed could lead to type-II errors. A solution is to swap ex ante friction for ex post accountability by requiring certified post-merger audits with penalties for firms that fail to deliver on promised efficiencies.

Some may assert that Europe’s challenges stem from broader macro factors—energy, demographics, geopolitics. While true, this underscores the importance of reducing friction in reallocating resources during structural challenges. The argument that “there were no prohibitions last year” misses the mark; investors focus on the median path rather than exceptional vetoes. The Commission's data indicate more notifications and decisions, but also increased complexity in enforcement and lengthy investigations. Therefore, the best reform is not to lessen scrutiny but to facilitate growth in cases with clear social benefits, allowing capital to account for the rules.

Europe’s Choice Is Urgency, Not Ideology

Europe has been debating for years whether it should allow major companies to compete against each other. This discussion distracts from a more pressing reality highlighted by the data: the continent's productivity is only operating at half its potential, not due to a lack of funding, but because of insufficient speed. In 2024, there was just a slight increase in hourly productivity; since 2019, the U.S. has seen significantly greater gains than Europe. Meanwhile, private equity firms hold a record amount of capital, poised to invest, improve, and expand. The issue lies in procedural delays. A system that prides itself on rare prohibitions but allows slow, uncertain processes for non-systemic transactions is not impartial—it hinders scaling due to delays. The solution is not to lower barriers; it's to open the gates for the right opportunities: consolidations that enhance productivity without gatekeeping or subsidies, accompanied by credible remedies and accountability after mergers. Make these pathways quick, reliable, and transparent. Maintain high standards where ecosystems or subsidies could jeopardize the single market. If Europe takes these steps, productivity metrics will start to show improvement. In a continent facing demographic constraints and abundant capital, this approach represents the most cost-effective growth strategy.

The original article was authored by Natalia Fabra, a Professor of Economics at Cemfi, along with two co-authors. The English version, titled "How to update the EU Merger Guidelines," was published by CEPR on VoxEU.

References

Alston & Bird. (2024, June 14). European Commission opens first M&A in-depth investigation under the Foreign Subsidies Regulation.

Bain & Company. (2025, March 3). Global Private Equity Report 2025.

Bruegel (Mariniello, M.). (2025, March 13). Reinforcing EU merger control against the risks of acquisitions by big tech. Policy Brief.

Dechert (DAMITT). (2025, January 30). 2024 Annual Report: Merger enforcement at low speed, Phase II durations at record highs.

Deloitte. (2024). Private Equity Confidence Survey—Central Europe. (Sentiment on regulatory barriers).

DG Competition, European Commission. (2025, April 9). Annual Activity Report 2024 (COMP_AAR_2024_final).

ECB. (2024). Labour productivity growth in the euro area and the United States. Economic Bulletin, Box article.

EY. (2024, June 19). Europe Attractiveness Survey 2024.

Eurostat. (2025, March 27). Productivity trends using key national accounts indicators. (Statistics Explained).

Kirkland & Ellis. (2025, January 16). 2025 EU Antitrust, FSR and FDI Update. (Merger statistics for 2024).

Norton Rose Fulbright. (2025). EU merger control and Article 22: The saga continues. (Impact of the CJEU’s September 2024 ruling).

Reuters. (2025, July 8). Booking tells EU court there was no compelling evidence to veto eTraveli deal.

Financial Times. (2025, Aug). EU trustbuster warns against ‘big is beautiful’ merger push. (Interview with Olivier Guersent).

European Commission—Competition Policy. (2025, August 1). Statistics on Mergers cases (PDF).

EIF—European Investment Fund. (2024). Private Equity Mid-Market Survey 2024. (Regulatory considerations as cross-border barriers).

Comment