Marking to Labour: Why Transparency Isn’t a Settlement Mechanism

Input

Modified

This article is based on ideas originally published by VoxEU – Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR) and has been independently rewritten and extended by The Economy editorial team. While inspired by the original analysis, the content presented here reflects a broader interpretation and additional commentary. The views expressed do not necessarily represent those of VoxEU or CEPR.

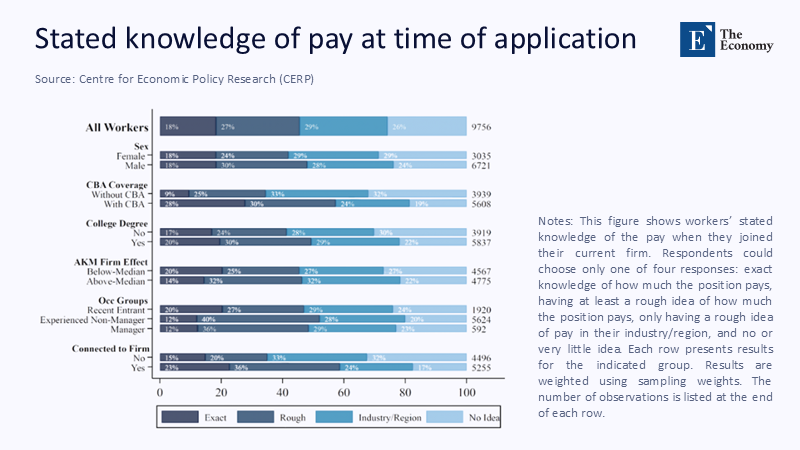

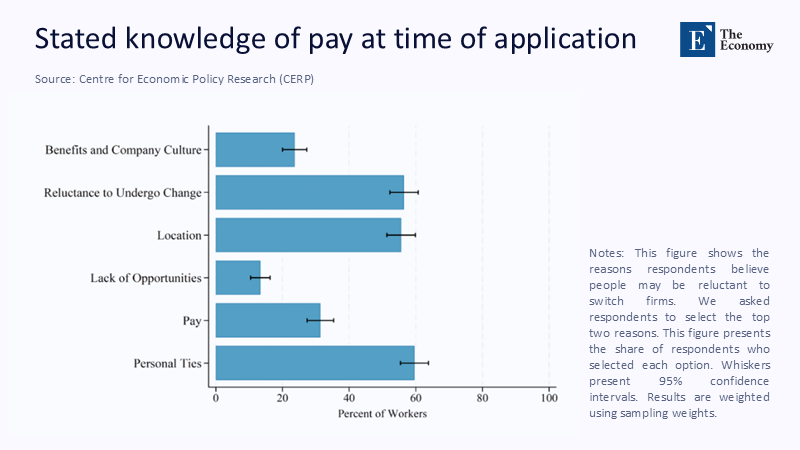

In advanced economies, we have made notable progress in indicating the "price" of work. As of May 2025, 59% of job advertisements in the U.S. on Indeed include salary information, an increase from just over half in late 2024; the UK stands out in Europe with about 71% of job posts revealing pay. However, job mobility is slowing down instead of speeding up: the U.S. quits rate is at 2.0%, the lowest it has been since 2016, excluding the initial pandemic shock, while the job vacancy rate in Europe has declined to 2.2% in Q1 2025 from 2.6% a year earlier. We have greater transparency but reduced turnover. Recent survey data from Germany highlights the contradiction: workers are frequently aware they could earn more elsewhere, yet they remain in their positions unless an external offer significantly surpasses a personal threshold that involves factors like commuting time, childcare arrangements, team connections, and the anxiety of making a switch. In financial terms, we refer to this as an adjustment cost. In labor policy, we often confuse a transparent display of market rates with an effective system for reaching agreements. Transparency is beneficial. It is not a solution in itself. This underscores the urgent need for comprehensive reforms that go beyond transparency to address the underlying frictions in the labor market.

Reframing the Analogy: From Mark-to-Market to Mark-to-Mobility

The conventional view assumes that if workers see the right price—an advertised wage—the market will update instantly. Financial markets do this because they have deep liquidity, negligible switching costs, and a robust settlement infrastructure. Employment relationships do not. Contracting for labour is not just a price; it is a bundle of expectations, routines, benefits, and social capital that must be dismantled and rebuilt. New evidence from an extensive German survey shows most workers are not in the dark; they are in the calculus. Many remain despite knowing higher wages are available because their reservation premium, which includes non-wage factors and risk, is not met. A policy that treats pay transparency as a cure-all will therefore disappoint. The more productive reframing is to view transparency as the quotation screen, not the execution venue. The task for policy is to compress the “bid-ask spread” of job change by lowering the non-price costs that separate posted offers from executed switches.

Measuring the Adjustment Wedge

Consider a simple counterfactual. If information were the dominant constraint, the expansion of disclosed pay should have lifted switching. From September 2023 to May 2025, the share of U.S. postings with pay information rose meaningfully, and European disclosure climbed as well, especially in the UK. Over the same window, quits flattened at 2.0% and vacancy rates drifted down. A back-of-the-envelope elasticity of quits with respect to transparency thus looks close to zero in the short run. That does not mean openness is irrelevant; it means its effect is mediated by a wedge composed of search time, risk of bad matches, loss of seniority, reset of benefits, and the fixed costs employers incur to reprice entire teams when one salary moves. A realistic policy model must therefore treat transparency as necessary but insufficient, with the binding constraint shifting to mobility and settlement frictions that information alone cannot dissolve.

What Benchmarking Misses: Hidden Frictions in Plain Sight

Even within firms, the data we surface is rarely the data we need for real-time adjustment. HR practitioners warn that pure salary benchmarking misleads in four recurring ways: titles often mismatch underlying duties; single datasets obscure dispersion across regions and functions; compensation decisions bundle benefits, progression ladders, and equity that surveys cannot capture; and point-in-time benchmarks fail to enforce internal consistency across roles. These are not trivia; they are micro-frictions that turn visible prices into noisy signals, raising the premium a worker demands to jump and the cost a firm faces to match. In aggregate, they behave like financial “transaction costs”: when they are high, even rational actors delay rebalancing, tolerating mispricing until the expected gains exceed the pain of recalibration. That is why pay transparency’s promise fades without reforms that make jobs more comparable, skills more legible, and pay architectures more portable across employers.

Monopsony, Licensing, and the Geography of Switching Costs

A second layer is structural market power. Contemporary research emphasizes that monopsony arises less from classic concentration than from search frictions: it is complex and costly to look, and easier for large firms to segment pay internally. Occupational licensing adds formal barriers—fees, waiting times, and duplicative credentials—that impede cross-border or cross-state mobility, while skills mismatches and place-based constraints amplify the inertia. OECD work underscores how mid-career workers face pronounced frictions and how skills gaps within firms persist even when vacancies abound, suggesting that coordination failures, not awareness, are binding. The policy implication is sober: disclosure can compress information asymmetry, but without mobility-enhancing reforms—licensing reciprocity, credential portability, and skills-first hiring—the adequate labour supply elasticity facing individual firms remains low, and wage “markdowns” persist. The result is slower diffusion of wage information into actual earnings than many transparency advocates predict. This highlights the crucial need for mobility-enhancing reforms to facilitate labor market mobility and reduce wage disparities.

Employers’ Menu Costs and the Team-Equity Constraint

Firms, too, face menu costs. Adjusting one worker’s pay cascades through compression concerns, equity bands, and collective agreements. Evidence on wage rigidity shows real adjustment lags when profitability is tight and labour intensity is high, precisely the settings in which external offers should bite. Add recruiting and onboarding costs, the risk of mismatch, and the need to defend internal relativities, and we see why managers do not “mark to market” daily. In practice, they bundle revisions into annual cycles, just as portfolio managers with high trading costs bunch trades. This is rational behaviour under frictions, not resistance to information. To accelerate pass-through, policy must reduce the cost of repricing teams—by standardizing job architectures, enabling safe disclosure within firms without legal hazard, and supporting tools that map external benchmarks to internal roles with statistical rather than title-based matching. This underscores the importance of reducing the cost of repricing teams to make wage updates more frequent and responsive to market changes.

Necessary but Not Sufficient: What the New EU Rules Do—and Don’t

The EU’s Pay Transparency Directive will force disclosure, reporting, and remedial action when gaps exceed set thresholds. That is a material step toward fairer pay, especially for closing gender gaps, and it will raise the floor of information quality across the single market. It will not, by itself, build the pipes that carry workers to better matches. Without faster recognition of qualifications across borders, better childcare capacity where shortages choke mobility, and incentives for employers to recognise skills acquired outside formal pathways, transparency may mainly reprice incumbents rather than enable reallocation. Policymakers should therefore treat the directive as an information backbone onto which mobility-enhancing measures are grafted: a clearinghouse for salary data linked to reciprocity in licensing, skills passports that cut validation times, and hiring subsidies contingent on demonstrated skills use rather than degree pedigree. Otherwise, we risk celebrating dashboards while labour markets remain sticky.

A Mark-to-Adjustment Program for Educators and Institutions

Education systems can reduce the wedge early by making skill signals more comparable and transferable. Universities and vocational institutes should publish competency transcripts in machine-readable formats aligned to sector taxonomies so that external benchmarks map cleanly to internal pay bands. Public agencies can co-finance “mobility micro-grants” that defray relocation, certification, or childcare costs when workers accept offers that advance their skills and earnings. Employers can commit to skills-first hiring and transparent progression ladders that minimise the fear of losing seniority. For older workers, targeted coaching and modular upskilling reduce switching risk and accelerate time-to-productivity, as recent OECD analyses recommend. Finally, regulators should encourage wage insurance pilots that cushion short-term earnings volatility during role transitions, allowing workers to accept moves that pay off over a two-year horizon. These actions do not replace transparency; they enable it to be clear, converting quotes into trades and information into mobility.

Anticipating the Objections

One critique is that more transparency compresses pay and dulls incentives. That risk exists in narrowly defined internal labour markets, but the external evidence is mixed and sensitive to context. Where monopsony power is strong, raising visibility can lift pay floors without obvious employment losses because firms face an inelastic labour supply at the job level. Another argument holds that compliance costs will burden small employers. That is precisely why reforms should simplify compliance via standardised templates and common job frameworks, reducing bespoke legal work. A final worry is that wage posting without productivity gains will fuel inflation. Here, the recent cooling in vacancy rates and wage growth suggests room to raise fairness without igniting a spiral, especially when paired with measures that expand adequate labour supply by lowering switching costs. A mark-to-adjustment policy complements macro-stability by improving allocation rather than simply raising averages.

Build the Clearinghouse

Pricing alone does not determine trade outcomes. Financial markets have long recognized that transparency without a clearinghouse creates false perceptions of liquidity. Labor policy is currently rediscovering this concept. In the last two years, there has been a significant increase in pay transparency, yet worker resignations have decreased and job openings have softened. The issue isn’t that transparency has failed; instead, we have neglected to implement mobility measures that minimize the non-price barriers to change. The way forward is practical: maintain the dashboards, but also standardize job structures, share credentials, invest in childcare and relocation assistance, and experiment with wage insurance to mitigate risk aversion that hinders potentially beneficial transitions. If we take these steps, the market will not only record prices; it will also adjust accordingly. Workers will identify pathways instead of pay ranges. Businesses will adapt compensation for teams without needing to dismantle them. And the information we've worked hard to disclose will finally perform the function we intended—facilitating a faster market for skills that matches the pace of modern economies rather than the slow rhythm of annual evaluations.

The original article was authored by Sydnee Caldwell, an Assistant Professor at the University of California, Berkeley, along with two co-authors. The English version, titled "Information and the labour market," was published by CEPR on VoxEU.

References

Azar, J. (2024). Monopsony in the Labor Market. RFF Berlin Discussion Paper 24031.

Bureau of Labor Statistics (2025). Job Openings and Labor Turnover—June 2025 (JOLTS). U.S. Department of Labor.

Caldwell, S., Haegele, I., & Heining, J. (2025). Information and the labour market. VoxEU/CEPR.

Cedefop (2024). European Skills Index 2024: Technical Report. European Centre for the Development of Vocational Training.

European Commission (2023). Directive (EU) 2023/970 on pay transparency. EUR-Lex.

Eurostat (2025). Job vacancy statistics: Q1 2025 developments. European Commission.

Exude Human Capital (2023). Why Salary Benchmarking Is Not Enough. ExudeHC Blog.

Hiring Lab, Indeed (2024). 2025 U.S. Jobs & Hiring Trends Report. Indeed Hiring Lab.

Hiring Lab, Indeed (2025). Salary Transparency in Europe: Building Trust, Closing Gaps. Indeed Hiring Lab UK.

Indeed (2025). Pay Transparency Across High-Earning Sectors. Indeed Newsroom.

OECD (2024). Employment Outlook 2024. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development.

OECD (2025). Employment Outlook 2025: Reviving growth in a time of workforce ageing. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development.

OECD (2025). Empowering the Workforce in the Context of a Skills-First Approach. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development.

Faia, E., et al. (2024). The Cost of Wage Rigidity. Review of Economic Studies, 91(1), 301–341.

Reuters (2025). UK job ads most likely in Europe to include salary details. February 11, 2025.

St. Louis Fed (2025). Quits: Total Nonfarm (JTSQUR). Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis (FRED).

Comment