Vietnam’s Low Fertility Before High Income: Rethinking Growth When Family Size Falls Early

Input

Modified

This article was independently developed by The Economy editorial team and draws on original analysis published by East Asia Forum. The content has been substantially rewritten, expanded, and reframed for broader context and relevance. All views expressed are solely those of the author and do not represent the official position of East Asia Forum or its contributors.

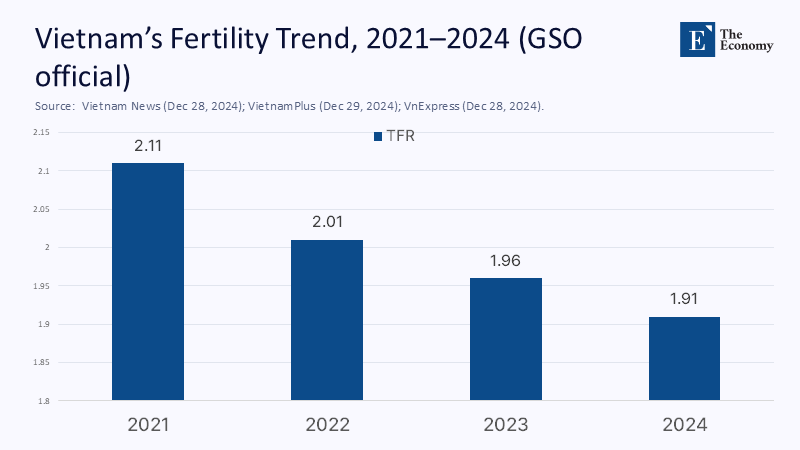

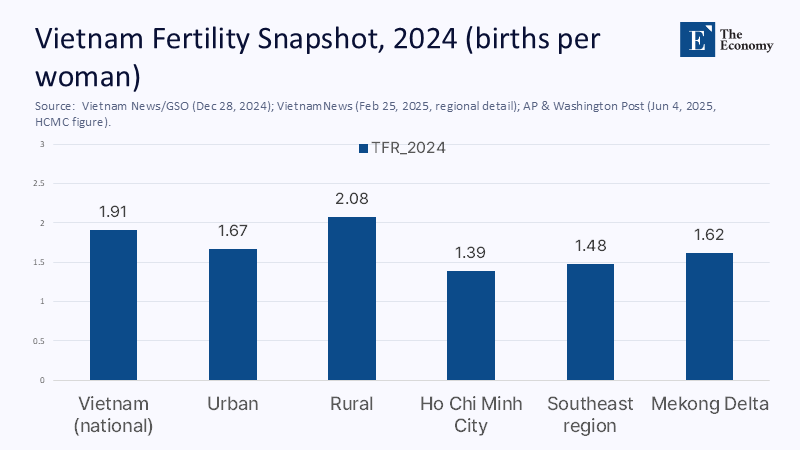

The key figure is not Vietnam’s GDP growth or export proportion; it is 1.91—the predicted total fertility rate for 2024—falling below replacement level and marking the lowest in the nation's history, even as the economy has not yet achieved high-income status. This statistic, which hides deeper issues, highlights the pressing nature of the situation: urban fertility stands at 1.67, with Ho Chi Minh City around 1.39, rates more characteristic of aging OECD countries than of a rapidly industrializing nation. The decline has continued even during the culturally “auspicious” Year of the Dragon and amidst relatively generous maternity leave policies compared to regional norms. The government has abolished its long-time two-child policy, yet the demographic decline remains unchanged. If Vietnam’s workforce reaches its peak in the early 2040s and subsequently diminishes, the typical scenario—where a youthful workforce drives export-led growth—will become less viable before the country achieves high-income status. The critical question is not merely why birth rates are decreasing; it is whether Vietnam can take advantage of a proactive fertility decline by reworking its care system, labor markets, and growth model instead of pursuing costly, low-impact pro-natal incentives.

A Reframe: Premature Aging, Not Post-Affluence Decline

Low fertility is often narrated as the endpoint of prosperity: first, you get rich, then you stop having children. Vietnam is reversing the sequence. The country’s per-capita income hovered around US$4,700 in 2024—middle-income, not affluent—yet its fertility is already below replacement and drifting downward in large cities. That timing matters. When fertility stalls before social protection systems mature, the costs of aging fall on families and informal networks rather than on robust public programs; care work concentrates in households, and women’s time becomes the scarcest factor in the economy. In that light, Vietnam’s problem is not a moral failing or a Western import, but a structural collision: modern urban costs and work rhythms arrived faster than care infrastructure and housing solutions. The consequence is what we might call “pre-affluence gray,” where birth decisions respond rationally to price and time signals in cities that outgrew their social services.

This reframing also clarifies policy priorities. If falling births were mainly a matter of cash, the cure would be simple. But evidence from Korea and a broad OECD literature suggests the elasticity of fertility to pure transfers is small, especially once rates dip below roughly 1.5. Vietnam should avoid a costly chase after marginal gains and instead focus on the bundle that most households optimize—time, career continuity, housing, and reliable care—while adjusting its growth model to rely less on perpetually expanding cohorts of young workers. This comprehensive approach is crucial in addressing the multifaceted issue of low fertility.

The Data: A Fast-Industrializing Country With Big-City Fertility Near 1.4

The recent numbers are stark and recent enough to matter for policy. National fertility fell to about 1.91 in 2024, the third straight year below replacement. Urban fertility was roughly 1.67 versus 2.08 in rural areas; Ho Chi Minh City recorded around 1.39, and Hanoi between 1.6 and 1.7. Meanwhile, female labor force participation is high for the region—around 69 percent—so any policy that sidelines women from work is likely to backfire. These shifts coincide with later marriages in the most extensive metro and a rapid urban cost squeeze. Taken together, the data describe a national average that masks metropolitan fertility compatible with the world’s lowest-fertility economies, but without their deep safety nets.

Policy has started to move, but cautiously. In June 2025, Vietnam abolished its two-child guidance after decades, aligning the law with demographic reality. Yet ending limits does not create childcare centers, reduce housing burdens, or shorten commutes. The care economy, which refers to the system of care services and support available within a society, remains thin: only about 22.7 percent of children were in pre-primary facilities in 2020, and social norms still assign caregiving to women—37 percent of those aged 26–50 and 77 percent of those 51+ say childcare is a woman’s duty. In this landscape, family size shrinks not because people “care less” about children, but because they see no feasible way to combine two full-time jobs, long hours, and scarce affordable care.

What Money Can—and Cannot—Buy: Lessons From Korea and the OECD

Two decades of extravagant spending in South Korea serve as a warning. Despite spending tens of trillions of won on cash, housing, and maternity benefits, Korea’s total fertility rate has remained around the lowest in the world, showing a slight increase to approximately 0.75 in 2024 from 0.72 in 2023, which is still well below replacement level. Both qualitative assessments and formal evaluations reveal a consistent issue: minimal financial support does little to alleviate significant barriers such as demanding work hours, rigid gender expectations in caregiving, unstable housing, and career penalties for mothers. Although the marginal price effect is real, it tends to be minor and often temporary. Vietnam cannot—and should not—overspend like Korea to learn this lesson the hard way.

Evidence from various countries supports this perspective. An OECD cross-national analysis indicates that increasing family transfers by PPP-$1,000 per child is associated with roughly a 1–1.6 percent increase in the total fertility rate; this is functional at the margin but inadequate to change trends where urban norms and time constraints prevail. Meta-studies and quasi-experimental research also show short-term increases from financial support or allowances, with impacts diminishing when fertility rates are already very low. The message for Vietnam is clear: if budgets are constrained, prioritize spending where impacts are greater—on time and services that enable parents to have the children they already express a desire for, rather than on attention-grabbing cash payments that have fading effects.

The Care-First Strategy: Prioritize Buying Back Parents’ Time, Not Just Their Intentions

A care-first approach emphasizes supply over slogans. Vietnam's commitment to early childhood education has not matched urban demand, leading to high private preschool costs that burden dual-income families. This results in long waiting lists, pushing parents toward informal solutions or delaying childbearing. Expanding access to affordable, quality childcare, especially for children under three, positively impacts mothers’ employment, family income, and the potential for having more children. Research shows that better childcare access enhances women's labor market outcomes and overall economic output.

Cultural norms also play a crucial role. Survey data indicate persistent gender expectations in caregiving, particularly among older generations. Policies can shift these norms by promoting a dual-earner, dual-carer model: enforceable paternity leave, employer-provided childcare incentives, and limits on excessive overtime. While Vietnam offers six months of paid maternity leave, paternity leave remains limited. Extending paternity leave can help balance intra-household responsibilities and reduce the “motherhood penalty.” Additional measures—safe commutes to childcare, predictable work hours, and support for part-time re-entry—can effectively translate policy intentions into real-life changes.

Can Vietnam Afford It? Yes—With Smart Priorities and Measured Ambition

The fiscal question is crucial. While Vietnam's public debt is around 34 percent of GDP, lower than many regional peers, its tax capacity is limited compared to wealthier OECD countries. Hence, spending must focus on high-impact areas. UNICEF recommends about 1 percent of GDP for early childhood care and education, but Vietnam currently spends less. With a projected 2024 GDP of US$476 billion, a 0.1 percent increase in childcare spending translates to about US$476 million. A phased increase to 0.7 percent over five years would amount to about US$3.3 billion annually—a significant but manageable goal through reprioritization and public-private partnerships.

These estimates serve as a guide, not guarantees, as costs depend on various factors. Initial capital spending should prioritize areas with low fertility rates and high female employment, followed by targeted subsidies that decrease with household income. Dedicated bond issuance can fund childcare infrastructure, while a shift from lower-impact tax incentives to care investments is justifiable for growth and equity.

Growth With Fewer Births: Productivity, Skills, and Selective Openness

Even with better care systems, Vietnam will not return to a 2.1 TFR anytime soon, and it should not premise its development on doing so. A realistic strategy treats low fertility as a structural parameter and builds growth on productivity, longer healthy working lives, and targeted migration. First, accelerate the move up value chains—particularly in electronics and advanced manufacturing—so that each worker produces more output. The World Bank notes Vietnam’s manufacturing-export engine remains strong; maintaining it in a tightening labor market will require automation diffusion, management upgrades, and skill formation aligned to firm demand rather than to credentialism. Second, keep older workers attached to the labor force by promoting mid-career training and flexible work, while investing in primary healthcare that lengthens healthy life expectancy. Third, pilot selective immigration schemes for skilled and semi-skilled roles in sectors with pronounced shortages, including eldercare—a labor-intensive field that will expand as the population ages.

These shifts are not a retreat from family policy but a complement to it. They reduce the opportunity cost of childbearing by creating workplaces where work schedules are predictable and wages are higher. They ease macro-level pressure by decoupling growth from ever-larger cohorts. Crucially, they avoid the ethical hazards visible elsewhere, where fear of low fertility has drifted into coercive or illiberal approaches. Vietnam’s removal of the two-child cap should be read not as a nudge to have many children, but as a commitment to reproductive autonomy. A care-first, productivity-oriented path honors that commitment while keeping the growth engine running in a world of smaller families.

Anticipating the Critiques—and the Evidence That Answers Them

Critics suggest Vietnam should adopt high-spending pronatalist models, but evidence warns against that approach. Korea's experience indicates that without changes in work hours, housing, and gender norms, large financial transfers yield limited benefits. OECD analysis shows better returns when spending supports time-related resources, like childcare and flexible leave, rather than cash alone.

Another critique posits that low fertility threatens growth, but growth accounting reveals that steady productivity growth can offset a smaller labor force in the future. Investment in human capital, technology, and management is key.

Additionally, concerns about fiscal overreach are addressed through international comparisons: Vietnam's low debt ratio and capacity for larger infrastructure issuances make a childcare investment feasible. This investment, representing 0.5–0.7% of GDP, could have significant benefits, especially for female labor supply. The guiding principle should be to subsidize time and support institutions, embracing a low-fertility future that prioritizes productivity.

From “Why So Few?” to “How to Thrive With Fewer”

Vietnam’s fertility rates dipped below replacement levels before the nation achieved significant wealth. This deviation from the typical pattern can either hinder growth or serve as a driver to modernize the social structures of a 21st-century economy. The statistics are clear: the national total fertility rate (TFR) is expected to be around 1.9 in 2024, with urban areas nearing 1.4, alongside persistent expectations that caregiving responsibilities mainly fall on women. The policy recommendations are equally straightforward. Discontinue the low-efficiency transfer race. Create affordable childcare in areas with high demand. Broaden and normalize paternity leave. Design work that honors personal time. Invest significantly in the care economy to make a substantial impact. And develop a growth model that accommodates small families, focusing on productivity, skills, and selective openness. When implemented together, these actions lower the time—and not just the financial—cost of having a second child that many parents are already considering, ensuring that prosperity does not depend on a difficult demographic resurgence. Vietnam can achieve high income levels with fewer births, provided it invests early and intentionally in the time and institutions that create harmony between family life and economic growth instead of conflict.

The original article was authored by Dr David Dapice, a Professor Emeritus of Economics at Tufts University. The English version, titled "Vietnam’s demographic decline narrows development pathway," was published by East Asia Forum.

References

Associated Press. (2025, June 4). Vietnam scraps 2-child policy as aging threatens economic growth.

Bloomberg. (2025, June 3). Vietnam ends two-child policy to stem falling birth rates.

Dang, H.-A. H., et al. (2022). Childcare and maternal employment: Evidence from Vietnam. World Development, 159. (Abstract page).

Early Childhood Development Action Network (ECDAN). (2024, June 10). Right to free early childhood education (Vietnam brief).

East Asia Forum. (2025, August 20). Vietnam’s demographic decline narrows development pathway.

Gender Data Portal, World Bank. (2023). Fertility rate, total (births per woman): Vietnam, 2023 = 1.9.

OECD. (2023). Fertility, employment and family policy: A cross-country perspective. (Working paper).

OECD. (2024). Society at a Glance 2024: Fertility trends across the OECD—Underlying drivers and the role for policy.

SingStat, Singapore Department of Statistics. (2025, May 7). Births and fertility: Latest data (Resident TFR 2024 = 0.97).

UNFPA Viet Nam. (2025, July 17). Population policy must reflect diversity and real-life experiences (statement noting 2024 TFR 1.91).

Vietnam General Statistics Office via Vietnam News. (2024, December 28). Việt Nam records its lowest birth rate at 1.91 in 2024 (urban 1.67; rural 2.08).

Vietnam Government & National Assembly via Washington Post. (2025, June 4). Vietnam drops two-child policy amid demographic concerns.

VnExpress. (2024, December 28). Vietnam’s 2024 birth rate hits historic low, defying year of the Dragon trends.

VnExpress. (2025, February 22). Vietnam’s birth rate among lowest in Southeast Asia.

Voice of Vietnam (VOVWorld). (2025, January 22). Vietnam’s total fertility rate hits record low (HCMC ~1.39; urban–rural gap).

World Bank. (2025). Vietnam country overview (GDP growth and structure).

World Bank. (2024). Vietnam: GDP per capita (current US$), 2024 ≈ $4,717; GDP 2024 ≈ $476b.

Yale School of Public Health (citing Vietnam Social Security). Social insurance in Viet Nam fully covers maternity leave.

Zhang, J. K., Kim, J.-K., & colleagues. (2024). Tackling South Korea’s total fertility rate crisis (review of policy efficacy). Journal of Men’s Health (via PMC).

Reuters. (2025, February 26). South Korea’s policy push springs to life as the world’s lowest birthrate inches up; 2025 spending plans.

Comment