When wages are fractured, so is unity: intra-occupational inequalities as a catalyst for urgent trade union empowerment

Input

Modified

This article is based on ideas originally published by VoxEU – Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR) and has been independently rewritten and extended by The Economy editorial team. While inspired by the original analysis, the content presented here reflects a broader interpretation and additional commentary. The views expressed do not necessarily represent those of VoxEU or CEPR.

In 2024, just 9.9% of wage earners in the US were unionized. And yet, 2023 saw the most strikes in the last 23 years, while in Europe in 2023 a panorama of wage conflicts unfolded—from transport to health—as workers chased prices that outpaced their wages. In June 2025, the public reaction to Jeff Bezos' wedding in Venice—in a city already suffocated by overtourism and service precariousness—was intense enough for receptions to move to more secluded venues, behind walls and controls. These events do not merely paint an image of "inequality". They show that sympathy for labor power is pervasive, while the institutions that turn it into a real bargaining weight are fragile and unevenly distributed. The crucial point is not inequality in general, but how the gap opens within the same profession—"intra-occupational pay inequality." When colleagues doing similar work are paid at different scales, cohesion cracks, organizing strategies are distorted, and bargaining units are fragmented. This is where the game of the new trade union force is played.

Radical refrain of causality: inequality within the profession, not only in society

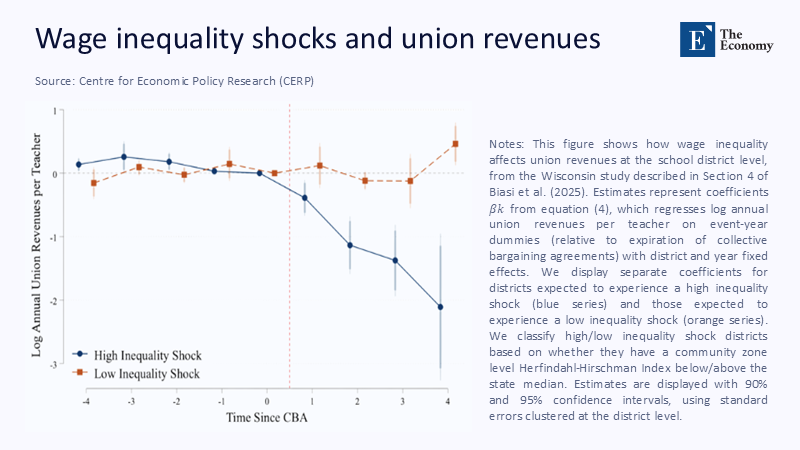

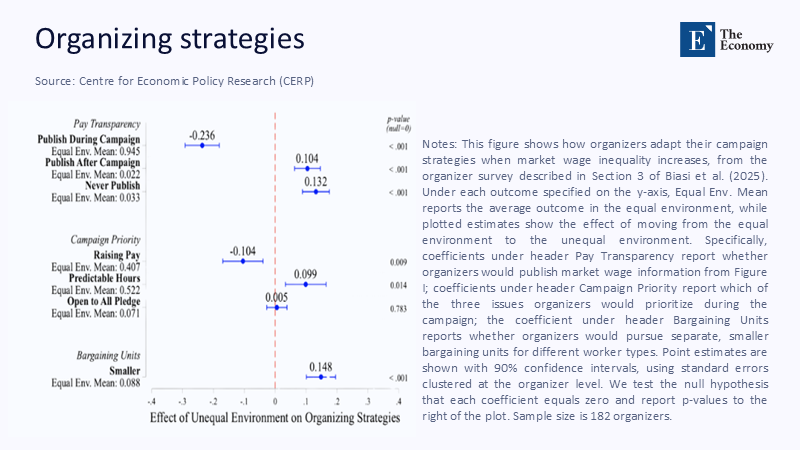

The usual conversation revolves around itself: unions squeeze wages, so fewer unions mean more inequality. Correct, but inadequate. Qualitative change today is the inequality within the same possible bargaining units: in the same role, in the same department, on the same scale. Modern empirical studies record that when wage dispersion within the profession increases, the highest paid people move away from collective action, organizers tend to smaller and more homogeneous units. At the same time, demands shift from wages to "neutral" benefits. This dynamic creates an "inequality trap": precisely where wage squeezes are needed, cohesion is more difficult, and the revenues of organizations are squeezed. A policy that targets the inside of the occupational distribution—not just the averages—is the only way to break the vicious circle.

Three mediators: culture, law, and socio-economic structure

If intra-professional dispersion is the spark, three mediators decide whether there will be a fire. Culture gives meaning to the unequal outcome—as a "risk prize" or as a breach of a social contract—and determines how displays of wealth are read in the public sphere. The law translates sentiment into action: recognition and extension of collective agreements, minimum thresholds, wage transparency, protection from retaliation, and conditions for a legal strike. The socio-economic structure defines the scenario: the severity of services with franchises and platforms, the concentration of employers, and the rate of inflationary shocks. Differences between countries are not just a matter of "temperament". It is an imprint of institutional hydraulics: where the coverage of collective agreements reaches universality, even strong vibrations are institutionally filtered; Where coverage is thin and every claim is rebuilt factory by factory, intra-occupational inequality breaks down the organization more easily.

What the comparative data 2023–2025 show

In the OECD, collective bargaining coverage ranges from almost universal (where expansion mechanisms operate) to less than one-fifth of workers in the US and Japan. This is not a detail: it determines whether a wage squeeze can be achieved without continuous mobilization. The European "boom" of 2023 was mainly a hunt for inflation, but within architectures that still yield high coverage, so agreements are quickly generalizing. In the US, on the other hand, long-standing sympathy for unions coexists with thin coverage and membership percentage stuck at 9.9%. Thus, political economy takes the form of "episodes": spectacular strikes and record increases—e.g., in the automotive industry—and then, quietly, the gap reopens. The discrepancies are not a matter of "temperament" but of coverage, rules, and sectoral composition.

The Venetian parable: display of wealth, unequal toil, different codes

The reaction to Bezos' marriage made the mediators visible. Protesters linked a billionaire's celebration to rising rents, overtourism, and precariousness in services. Authorities and organizers moved events to secluded venues with enhanced security. In the European public sphere, the display of wealth was read as a political act in a city where workers struggled to find shelter and stable wages. If the same were done in an American town, the spectacle would likely provoke more gossip than political assessment—not because egalitarianism is lacking, but because the institutional channels that translate sentiment into generalized wage scales are missing. The example is not about "envy", but about the ability to translate symbolic episodes into fixed thresholds.

Micromechanics of the workplace: equal role, unequal pay

Workers are not compared to the national income distribution; they are compared to their neighbors. That is why the dispersion within the profession is so corrosive. In Hollywood, writers saw residuals evaporate in the age of streaming, while a minority of top names reaped oversized pay; An information experiment during the 2023 strike showed that highlighting inequality reduced the belief that demands "benefit everyone", especially the highest paid. In American car factories, two-speed systems made veterans see newcomers doing the same job at much lower wages; The 2023 deals collapsed tiers, gave double-digit increases, and reinstated ATA clauses. In Amazon's warehouses, the first successful union campaign in the US flourished in an area where shifts in hours, safety, and pay intersected with high staff mobility—cohesion was built around elementary floors.

Scale and direction: what the indicators say

Two events anchor the conjuncture. First, union density in the US has remained relatively stagnant in 2024 at 9.9%. Second, the action was concentrated where the intra-occupational dispersion intensified after the inflationary shock. In 2023, strikes in the US skyrocketed, while in Europe, central conflicts ran into transport, education, health, and manufacturing. The gains were substantial: in the automotive industry, three-year base increases reached about a quarter, with 11% ahead and cumulative results pushing the top even higher, especially with ATA. At the same time, in early 2025, the momentum in favor of the low-wage weakened, with the lowest wages rising to multi-year lows. Without institutional tightening, the gap is expected to reopen as the market cools.

Culture is not an alibi: measurable norms and public mandates

It is tempting to attribute differences to "national temperaments": Americans honor businessmen, Europeans honor equality. The data is more complex. In 2024 surveys, around two-thirds of adults in 17 G20 countries supported higher taxation on the very rich for social purposes, while in the US, union acceptance remains high. The gap is not in the intention, but in the means. The new European directive on "adequate minimum wages" has reignited strategic discussions, but it is based on a common assumption: sectoral frameworks that re-equip power in low-paid services. In the US, reforms need to leverage multi-employer regulation, public procurement, and licensing to scale standards. Culture shows how a "spectacle wedding" is interpreted; The law decides whether this interpretation becomes a salary scale the following month.

Technology and structure: AI, platforms, and the new salary map

Technology does not widen inequality linearly. In an analysis of 19 countries, occupations with greater exposure to AI technologies over the past decade have seen slower growth in intra-professional dispersion—possibly because automation has replaced some high-paying tasks while increasing demand for complementary roles. At the same time, "platforming" and franchising have weakened internal hierarchies and widened the dispersion, as they fragment work and transfer risk to the worker. In an environment of inflationary shocks, ad hoc "bonuses" and personalized offers—rather than transparent scales—magnify the dispersion. Policy can steer the technology shock to a squeeze by setting universal pay transparency, mandatory narrow scales per role and tier, and linking AI adoption to evolution scales, not displacement.

Comparative Note for China and Southeast Asia

It is often concluded that China and parts of Southeast Asia "tolerate" inequality. The best explanation is institutional. In China, the trade union system is dominated by a federation, while independent organizations are limited; collective confrontations appear as local protests over debts, layoffs, or security, and rarely translate into generalized salary scales. Recordings show an increase in strikes/protests in 2023–2024, especially in construction and manufacturing, but without the mechanisms that turn mobilization into lasting rules. In many Southeast Asian economies, rapid industrial transformation goes hand in hand with weak or fragmented collective structures, so public reactions to a show of wealth are more reminiscent of the US than continental Europe: the discomfort exists, the outcome depends on whether the law supplies the lost "mechanism."

Policy architecture: how to break the "inequality trap"

Intra-occupational dispersion must be treated as a first-class macroeconomic risk. Three movements change trajectory. Firstly, universal transparency of remuneration with binding, narrow scales by role, grade, and place: transparency without scales only consolidates dispersion; The scales give teeth. Second, extending coverage where it is thinner, with multi-employer/sectoral arrangements to highly mobile services—hospitality, logistics, care—leveraging public procurement, tax incentives, and licensing to extend agreements to non-signatories. Third, automatic stabilisers in contracts: ATA clauses when inflation outstrips wages; anti-tiering clauses that erase 'two speeds'; Evolution rules that abolish the "temporary" after a specific term of office. It is not a theory; It is the institutional mirror of what we see in practice.

Practical implications for Secondary/Tertiary, health, and logistics

In education, administrations must now map the TA/EDIP/hourly wage scales. If the same roles are paid differently per department, publish scales and standardise the development before the next round of negotiation; The measure will lower the temperature and increase confidence. In hospitals and care, abolish "temporaries" that have become permanent with rapid regularization and parity of benefits; The examples of the automotive industry show how the deconstruction of tiers regains legitimacy. In logistics and retail, experiment with multi-employer forums where hours and security negotiate along with wages—"benefits" unite. Still, they need to be tied to precise scales so they don't replace pay. Everywhere, connect AI projects with progression scales and training credits so automation moves people upwards, not outwards.

Anticipating objections: incentives, "markets" and political will

First objection: intra-occupational dispersion is a symptom, not a cause; Globalization and technology are making gaps "inevitable." The answer is that the very mechanics of organization change when the gap within the unit opens—high-wage earners move away and demands shift, even when the average wage does not change (Biasi et al., 2025). Second objection: wage squeeze kills incentives. The solution is design: scales tied to role, tenure, and measurable performance keep "tournaments" where needed, cutting arbitrary differences that breed cynicism—third objection: society is too divided for ambitious reforms. The data show majority support for progressive taxation and long-term union acceptance, while the European experience of recent sectoral negotiations has produced substantial convergence without chaos (Ipsos/Global Commons Alliance, 2024; Gallup, 2024· Eurofound, 2024). The obstacle is not the will; It is the absence of channels that make collectivity routine.

From wage gaps to social peace

The initial figure—9.9%—is not a verdict on social mood; It is an indicator of institutional planning. The action is already happening: strikes at perennial highs, rewritten scales, public reactions that move even the ritual of a lavish ceremony. Whether the sparks will become a permanent convergence of wages depends on whether politics governs the distribution within the professions. If we make transparency universal and essential, expand coverage through sectoral frameworks, and incorporate automatic stabilisers into contracts, we will turn occasional indignation into predictable justice. If we ignore the "lens" of the profession, we will recycle the same cycle: noise without a settlement, news headlines without floors, and "show ceremonies" that give rise to rituals of rage that fade away on Monday. The road to social peace passes through the ladder of wages at eye level. Narrow it down where people work and the rest—innovation, investment, and even the public reception of wealth—find firmer ground.

The original article was authored by Barbara Biasi, a Visiting Assistant Professor at Einaudi Institute for Economics and Finance (EIEF), along with three co-authors. The English version of the article, titled "How wage inequality affects the labour movement," was published by CEPR on VoxEU.

References

Amazon Labor Union. (n.d.). The first Amazon union in US history.

Associated Press. (2025, June 23–28). Reporting on protests and security measures at the Bezos-Sánchez wedding in Venice.

Biasi, B., Cullen, Z., Gilman, J., & Roussille, N. (2025, August 16). How wage inequality affects the labour movement. VoxEU/CEPR.

Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2025, January 28). Union Members—2024 (USDL-25-0105).

Business & Human Rights Resource Centre. (2024). China: Worker protests recorded by China Labour Bulletin doubled in 2023; manufacturing incidents up tenfold.

Economic Policy Institute. (2025, March 24). Strong wage growth for low-wage workers bucks the historic trend (State of Working America Wages 2024).

Eurofound. (2024, July 29). Labour disputes across Europe in 2023: Ongoing struggle for higher wages as cost of living rises.

Gallup. (2024, July 15). Labor unions: Historical trends and party alignment.

Global Labour University. (2024). Labour perspectives on China (Working Paper No. 60).

Ipsos / Global Commons Alliance / Earth4All. (2024, June 24). Tax the rich: Majority support across 17 G20 countries.

OECD. (2024a). What impact has AI had on wage inequality?

OECD. (2024b, July 1). OECD Employment Outlook 2024.

OECD. (n.d.). Collective bargaining and social dialogue.

Reuters. (2023, October 9). Hollywood writers union ratifies three-year labor contract after strike.

Reuters. (2023, October 30; November 20). UAW reaches deal with GM; UAW clinches record Detroit deals, turns to organizing.

Reuters. (2024, February 21). US labor strikes jump to 23-year high in 2023.

Reuters. (2025, June 24 & 29). Bezos' Venice wedding party moved; Venice protests target Bezos.

The Guardian. (2025, April 13; June 24). No union and forget staff toilet breaks…; Jeff Bezos alters Venice wedding plans after threatened protest.

US Federal Reserve Board. (2024, April 16). Tapping the Brakes: The Effect of the 2023 United Auto Workers Strike on Economic Activity (FEDS Notes).

Wall Street Journal. (2025, August 13). The Era of Big Raises for Low-Paid Workers Is Over.

Comment