Break the Rule, Build People: Why Labor — Not Capital — Determines the Fate of Downstreaming

Input

Modified

This article was independently developed by The Economy editorial team and draws on original analysis published by East Asia Forum. The content has been substantially rewritten, expanded, and reframed for broader context and relevance. All views expressed are solely those of the author and do not represent the official position of East Asia Forum or its contributors.

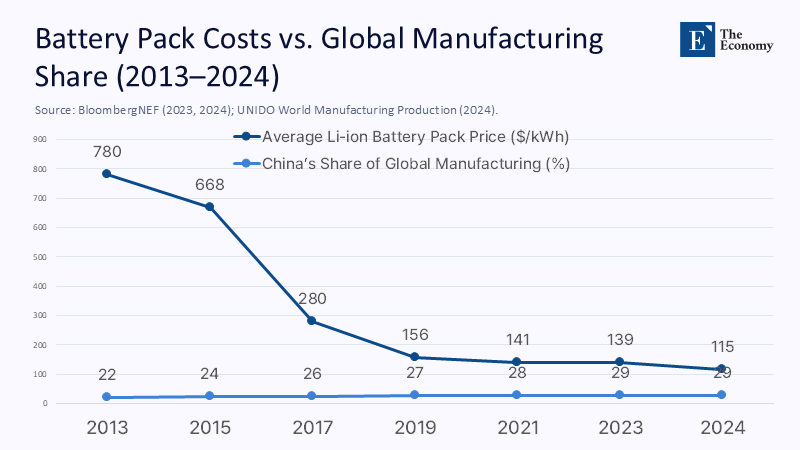

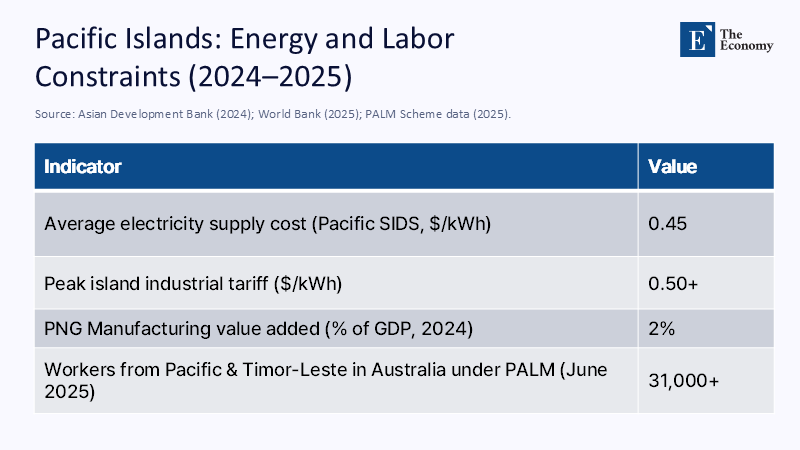

In 2023, China produced about 29% of global manufacturing output—nearly a dozen units ahead of the U.S.—after two decades of cumulative learning‐through‐action that squeezed battery pack prices around $139/kWh in 2023 and still 20% lower, to around $115/kWh, in 2024 (BloombergNEF 2023; 2024; IEA 2024· UNIDO 2024–2025). These falls were not a miracle of subsidies but a numerical experience on a continental scale. Now contrast it with the Pacific: the average cost of electricity on island grids hovered around $0.45/kWh in 2024, a multiple of East Asia's industrial tariffs, while the labor shortage is so severe that, in June 2025, over 31,000 workers from the Pacific islands and East Timor were working in Australia through the PALM program (ADB 2024; PALM 2025). The gap is instructive. Downstreaming isn't just about funding foundries or export bans. It is a race to accumulate productive knowledge embedded in people. Without a deep, renewable pool of skilled labor, attempts to "rupture" the comparative advantage will only momentarily bend it before it returns to its original position.

Refrain from the discussion: comparative advantage as a skill, not as a destiny

Breaking the comparative advantage for long-term benefit is not a suicidal attack on price signals; it is an investment position in favor of capabilities. The classical view treats it as a function of resources and wages. Modern reality shows that advantage is learned, aggregated, and routineized in businesses, supply chains, and training systems. The purpose of downstreaming policy is to create the conditions for a nation to become good at what it is not today. This requires institutional technology: iterative public-private problem-solving, conditional support, and uninterrupted workforce formation. The newer literature on the economics of industrial policy converges on this point: the rare influx is not money but coordination and performance governance (Juhász, Lane & Rodrik 2024). Where initiatives succeed, they tie reinforcement to measurable performance milestones and feedback loops between businesses, regulators, and training providers. Where they fail, they subsidize "irons" without cultivating the skills and managerial routines that make the "irons" sing. In short, factories are depreciating; people are paying interest.

The success or failure of downstreaming is judged by a stubborn, non-marketable input: time in practice. Learning curves—from 20th-century aeronautics to today's batteries—show that unit costs reliably fall whenever cumulative production doubles. The mechanism is not secret; it is a thousand minor improvements by workers and engineers who have seen ways of failure and corrected them. That is why countries that "invade" the wrong sectors can, with persistence, fix them. The prerequisite, however, is scale and persistence in the development of human resources. This is exactly what the pioneers possess: thick labour markets, dense networks of suppliers, and training programmes tuned into the production process itself. These are the elements that resource-rich incoming economies lack the most—and they are not imported with turnkey equipment.

The scale of the pioneers: learning curves, clusters, and China's relentless efficiency

The reason why today's leaders are difficult to displace is the accumulated experience on a national scale. China alone accounts for almost a third of global manufacturing and continues to grow manufacturing at rates of around 6–7% in 2024, while others slowed down (UNIDO 2024–2025). This scale fuels cost learning in batteries, photovoltaics, and electronics, with array prices falling to ~$115/kWh in 2024, confirming the "learning by action" hypothesis that modern research highlights. The result is a deep, self-reinforcing trench: lower costs bring in more orders, orders train more workers, and trained workers offer further cost and quality improvements. Convergence is possible, but it is no longer about equalising wages; it is about equalising accumulated knowledge of processes.

Crucially, the 'course' is integrated into ecosystems: supplier networks, test labs, specialized logistics, and vocational training. Economic complexity research shows that diversification into related, more complex products correlates with future growth and innovation. Translation: the fastest rise in the value scale occurs next to what a country already knows how to build. When newcomers attempt to jump into heavy downstreaming away from their skills front, they pay 'tuition fees' in downtime, skewed product, and imported supervisory staff. This 'teaching' is rarely adequately costed. And as pioneers relentlessly improve their operations, the goal moves. The policy conclusion is clear: to break the comparative advantage, you must fund the patient acquisition of implicit knowledge—not just the purchase of machinery. This requires patience and understanding of the time it takes to build this knowledge.

The Indonesian lesson: a daring experiment meets the gravity of skills

Indonesia's experience serves as a powerful lesson. Following the ban on the export of crude nickel, it attracted massive investment in nickel processing and battery materials, with dozens of foundries being erected or planned. The result is mixed. On the one hand, the export basket quickly shifted to processed metals and EV-friendly intermediates, showcasing the potential for success in downstreaming. On the other hand, the wave of new production capacity contributed to the fall in international nickel prices to multi-year lows, causing suspensions and layoffs from Australia to the Indonesian foundry parks themselves. The lesson is not that downstreaming is doomed, but that even large economies of capital and deposits stumble upon capacity bottlenecks when attempting to squeeze decades of learning into a few years. This underscores the importance of learning from past experiences and being prepared for the challenges that may arise.

Take a closer look at the work. Reports and corporate disclosures outline teams that combine experienced foreign supervisors with less experienced local operators, with the assistance of interpreters—an efficient short-term bridge, but one that means subtle domestic experience. Some complexes employ tens of thousands of workers in multiple units, while a single mature foundry historically required hundreds of workers. These snapshots capture the raw arithmetic of staffing: heavy vertical integration is highly intensive in human resources in its booming years. Suppose Indonesia—the region's scale player with decades of industrialization—continues to rely heavily on imported know-how while struggling with cyclical commodity prices. In that case, it sets a sober benchmark for smaller, poorer, and more remote island states envisioning similar leaps.

The limitation in the Pacific: small working tanks, expensive kilowatt hours, and the numerical staffing

For the Pacific islands, the binding constraint is not fixed capital investment but capacity—human and infrastructural. Energy first: the average electricity cost of around $0.45/kWh, with tariffs exceeding $0.50/kWh on some islands in 2024, means that every hour of machine operation is an accurate "learning". At the same time, small domestic labour markets are actively drawn from Australia and New Zealand through kinetic programmes. In June 2025, more than 31,000 Pacific and East Timor islanders were working in Australia through PALM, with flows from countries such as Solomon Islands increasing sharply after 2022. Mobility brings critical income and skills—but it also removes rare artisans, instrument specialists, and supervisors from domestic industries when local downstream ventures need them.

Add the operating environment as well. Manufacturing as a percentage of GDP hovers around 2% in Papua New Guinea, the region's largest labor market. Logistics costs for small island developing states are structurally high; ports face capacity and resilience issues; the risk of natural disasters often disrupts transport and electricity supply (World Bank 2024–2025). Educational diagnostics show older students and achievement gaps in several countries, making it challenging to transition from technical training. None of these obstacles is insurmountable. But altogether they imply two complex numbers. First, staffing even a medium-sized metallurgical plant probably needs hundreds of skilled operators and technicians at start-up — a figure that far exceeds the annual "output" of most national VET systems. Secondly, the maturation of this body at a professional level requires years of rotations and shifts, not months. When electricity is expensive, the cost of on-site learning increases; when workers are few, every departure throws back the metronome of learning.

The sequence of rupture: an industrial policy that puts work first

If the goal is to "break" the comparative advantage, the order of the moves matters. Countries don't jump learning curves; they climb them. This implies a labour-centric industrial policy architecture. The central move is to tie every resource dollar (resource rents) and every downstream investment license to specific, time-binding workforce-building milestones. Reciprocities should include co-financed apprenticeships, in-factory training centres, supervisor localisation targets, and co-managed curricula with public VET providers. It is not an ideology; it is an empirical finding: modern assessments show that policies succeed when they institutionalize public-private problem-solving and the reward condition—support in exchange for the acquisition of competences.

The method must be realistic in terms of time. Learning-by-practice studies in advanced energy processing show sharp early cost reductions only where the cumulative output doubles rapidly; in small markets, the doubling step is slow. The policy driver for small economies is therefore concentrated scale: standard regional training streams, multinational apprenticeships, and standardised certifications so that skills are mobile across units and borders. A "Pacific Skills Pact" could federate VET providers and anchored employers in fisheries, food processing, and energy materials, so that trainees who "learn" at Indonesian or Australian facilities return to guaranteed positions at home with recognised qualifications. Finance ministries can incorporate these pacts into tax credits and absorption contracts, so that when the following construction site is dug, human resources arrive with it.

What to build now: "skills today, industries tomorrow" instead of "heavy downstream now"

The work-first strategy doesn't reject downstreaming; it regulates it. In the short term, resource-rich island states would have to target capacities adjacent to their current advantages, where the skill intensity is high. Still, the capital intensity and the minimum effective scale are moderate. In practice, this means upgrading to cold fish processing chains with digital quality systems, marine nutraceuticals and specialty foods, woodworking/engineered wood for durable constructions, as well as repair-upgrade services aligned with existing transit centers. These "hearths" share a characteristic that heavy metallurgy does not have: they scale first with humans and then with megawatts. In addition, they build managerial routines in documentation, certification, and traceability, which are directly transferred to more complex units. Over time—as labor flows fatten and electricity costs fall with renewables and storage—the downstreaming ladder climbs steadily, not one-size-fits-all (ADB 2024; World Bank 2024–2025).

Indonesia's current trajectory remains useful as a learning curve. Even with its size, the country was hit when international nickel prices fell, exposing how thin the margins are in the first steps of vertical integration. Many projects went ahead because national policy created credible signals of absorption and complementary investment, but day-to-day operation was based on imported supervision and long training cycles. For smaller economies, the arithmetic is even trickier. If you can't guarantee steady "lines" of trained operators every year, the cost of downtime and reprocessing will swallow up any tariff protection or subsidy.

Counterarguments and why they don't stand

A frequent counterargument says that automation will eliminate the limitations of work. If "robots" run the factory, why not go straight to high-value-added refining? The problem is that automation is transforming the synthesis of skills, but it does not abolish it. Highly automated installations require even denser concentrations of technicians, special instruments, mechanical processes, and maintenance planners—especially in the upstream phase when fault trees are still being discovered. Another counterargument argues that foreign partners can supply the skills indefinitely. In practice, long-term dependence on imported supervisors becomes a ceiling for in-house learning: expat echelons rotate, implicit knowledge is disseminated, and incentives for local training flows are attenuated. Experience from Indonesian foundry parks—with small nuclei of experienced foreign leaders and large local groups—shows a functional transitional model, not a permanent solution. Without explicit localization goals, the transition is bogged down.

A final counterargument assumes that high electricity costs will quickly fall with renewables, making downstreaming economical much sooner. Cheaper clean energy will help, but the price is only one dimension of system adequacy. Island networks need to add reliability, storage, and industrial-grade power—all of which require capital, institutional capacity, and time (ADB 2024; World Bank 2024–2025). In the meantime, logistics and resilience to natural hazards remain binding. Global experience still says that the fastest returns come when countries diversify into related products, deepen managerial skills, and then step by step into heavier processes as human capital is compounded.

The Great Rift: People Before Factories

The impressive map of global manufacturing—and the steep drop in battery costs—tells a simple story: scale plus learning prevails over simple endogenous endowments. Asia's leaders didn't just have a comparative advantage; They created it by training armies of workers, repeating processes, and absorbing early losses that buy experience. Island and other resource-rich backward states can indeed break their inherited advantage in raw materials, but the lever is labour. With average electricity costs still high and skilled workers so scarce that they are exported en masse, any push into heavy vertical integration that outpaces human resource formation will disappoint. The solution is not to surrender to the status quo; it is the serialization of the rupture: co-investing in people first, co-investing in learning through conditional partnerships, and pooling scale through regional skills pacts that feed a predictable "series" of technicians and supervisors. When the people arrive, the factories will follow. Until then, every public euro must be judged by a single test: does it accelerate and escalate human capacity? If not, it does not break the comparative advantage. It maintains it.

The original article was authored by Dr Hilman Palaon, a Research Fellow at the Lowy Institute in the Indo-Pacific Development Centre. The English version, titled "Why downstreaming policies in Asia struggle to deliver," was published by East Asia Forum.

References

Asian Development Bank (ADB). (2024). Pacific Economic Development (ADO update)· Pacific Renewable Energy Investment Facility (average supply cost ≈ $0.45/kWh).

Annual Reviews — Juhász, R., Lane, N., & Rodrik, D. (2024). The New Economics of Industrial Policy.

BloombergNEF. (2023). Lithium-ion battery pack prices hit record low of $139/kWh.

BloombergNEF. (2024). Battery pack prices fall further to ≈$115/kWh.

Financial Times. (2025). Indonesia's big bet on nickel sours as global prices tumble.

Harvard Growth Lab / Atlas of Economic Complexity. (2023–2025). Economic complexity datasets and rankings.

International Energy Agency (IEA). (2024). Batteries and Secure Energy Transitions.

Indonesia — Ministry/IEA policy note. (2022). Prohibition of the export of nickel ore (in full force since Jan. 2020).

Lowy Institute. (2025). Indonesia's green industrial policy and the downstreaming dilemma.

National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER). (2024–2025). Learning-by-doing in the global EV battery industry (multiple studies).

PALM Scheme (Australia DEWR/DFAT). (2025). PALM scheme data portal· Quarterly data report, June 2025.

Reuters / Reuters Plus. (2024–2025). Indonesia's trade, FDI and "half-trillion-dollar move up the value chain".

United Nations Industrial Development Organization (UNIDO). (2024–2025). Industrial Development Report 2024· World Manufacturing Production Q2–Q4 2024.

USITC. (2024). Indonesia's export ban of nickel: downstream production impacts.

World Bank. (2024–2025). Pacific Economic Update· Manufacturing value added (% of GDP), Papua New Guinea (~2%)· Maritime & transport for SIDS.

Comment