When Tariffs Teach: Why Diversification Is Now an Education Policy Problem

Input

Modified

Tariff shocks don’t halt trade—they reroute it, reshaping supply chains Those shifts hit education budgets, curricula, and partnerships, demanding “diversification-ready” systems Train for regulatory and logistics literacy, hedge procurement, and build cross-border academic ties

In a single year, Canada’s dependence on the United States as an export market fell by ten percentage points—dropping from 78% to 68% of total exports between May 2024 and May 2025—yet the surge in shipments to the rest of the world, up roughly 42%, still failed to fill the hole left by the weaker U.S. entirely. That stark arithmetic captures the new terrain for countries on the wrong side of U.S. tariff policy: most are not capitulating; they are racing to reroute. The educational stakes are high because diversification is not only a trade strategy, but also a skills, financing, and institutional strategy. When trade flows shift to new corridors, curricula, training pipelines, research priorities, and even campus revenue models must adapt accordingly. In this moment, the question for education leaders is not whether tariffs are good or bad economics. It is whether systems can equip students, teachers, and institutions to thrive in a world where trade diversion—shifts toward third-country suppliers and markets—is the dominant response to policy shocks. This highlights the importance of adaptability in our education systems.

Trade Diversion Isn’t a Footnote—It’s the New Syllabus

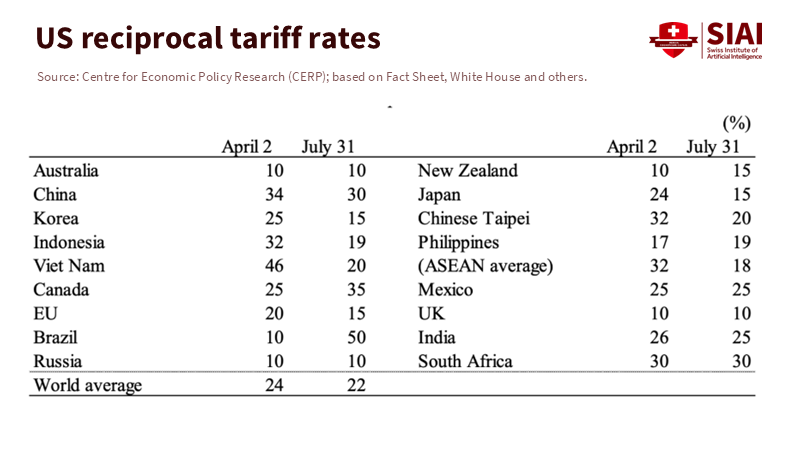

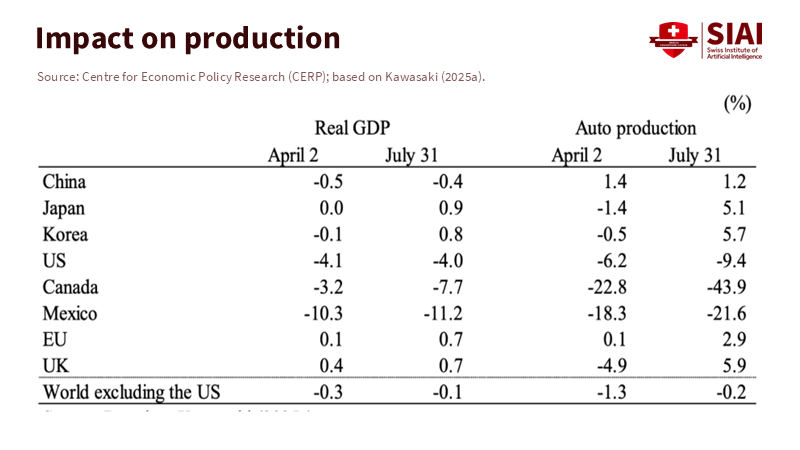

The core empirical point is settled: tariff hikes cut bilateral trade but reallocate it to third parties. A recent computable general equilibrium analysis finds that the 2025 U.S. tariff package lowers U.S. real GDP by around 4%, hits Canada and Mexico harder because of deep supply-chain linkages, and simultaneously boosts output in some economies that strike tariff accommodations—classic diversion. The first Trump-era tariffs already showed the pattern: U.S. imports from China fell, but purchases shifted to North America and Asia; domestic substitution was limited. For campuses, that means demand for understanding 'rules-of-origin '- the criteria needed to determine the national source of a product, customs compliance, and 'multi-standard quality assurance '- the ability to ensure that products meet the standards of multiple countries, becomes as foundational as Excel. We should stop treating trade theory as an externality in teacher training and treat it as the scaffolding for course design in business, logistics, engineering, and public administration programs.

A second implication follows from policy process, not just policy levels: uncertainty itself functions like a tariff. In early 2025, volatility in U.S. imports rose even before new measures took effect as firms scrambled to hedge, reroute, or front-load. UN trade analysts warn that unpredictability now drives up costs and chokes off investment—pressures that cascade into public budgets and household incomes. Education systems—heavily reliant on predictable tax receipts, donor funding, and family contributions—feel this in delayed capital projects, hiring freezes, and enrollment risk. Academic leaders do not need perfect foresight about tariff schedules; they need operational competence to run teaching and research in a high-variance environment. That makes strategic planning and supply-chain-aware budgeting urgent parts of the professional toolkit for superintendents, deans, and bursars.

Finally, the instrument mix has widened. The U.S. is not only adjusting base rates; it is targeting strategic nodes—EVs at 100%, semiconductors and solar at 50%, and critical minerals at 25–50%—with further revisions announced through 2025. That granular design amplifies the education impact because talent pipelines in automotive, energy storage, photovoltaics, and materials science will feel sharper, sector-specific shocks. Program directors who assume that “trade policy” is a backdrop will miss the way course enrollments, internships, and lab partnerships swing when one tariff line, not the entire macro picture, moves.

Three Paths to Diversification: China, Canada, and the LLDCs

China entered 2025 better prepared than most, having spent half a decade building options: deeper Belt and Road logistics, alternative shipping routes—up to and including trials of Arctic feeder services—plus a diplomatic push across ASEAN, the EU, and Brazil. During the March “Two Sessions,” Beijing reaffirmed its plan to broaden partners; by mid-year, official trade data pointed to weaker U.S. flows but gains to the EU and ASEAN, consistent with an aggressive diversion strategy. Even commodity sourcing reflects the pivot: soybean purchases leaned harder into South America, and rail-based links through Chongqing marketed “Suez-on-rails” speed for higher-value goods. For educators, the lesson is clear: prepare students for 'multi-route trade '- the practice of using multiple trade routes to diversify risk and reduce dependence on a single market, where logistics intelligence and standards navigation matter as much as language skills. Cross-listed modules that pair supply-chain analytics with regional political economy are no longer electives; they are employability.

Canada’s story shows the limits of diversification when geography and integration run deep. Exports beyond the United States climbed, with the U.K. briefly overtaking China as destination number two and headline growth in shipments of gold, energy, and pharmaceuticals to a wide set of allies. Yet even a ten-point drop in the U.S. share left the country structurally tethered to American supply chains; value-added manufacturing remains calibrated to U.S. standards, buyers, and just-in-time corridors. For colleges and polytechnics, this suggests a dual curriculum: maintain NA-specific competencies (USMCA rules of origin, automotive APQP, FDA/Health Canada dual compliance) while developing fluencies in the Asia-Pacific, EU, and Commonwealth markets. A campus that graduates engineers who can retool a plant for EU CE marking or ASEAN sanitary and phytosanitary protocols will help firms translate diversification talk into booked orders.

The most brittle position belongs to landlocked developing countries (LLDCs). UNDP’s analysis quantifies the vulnerability: for every one-percentage-point increase in tariff rates, LLDC trade volumes fall an additional four percent compared with non-LLDC peers—on top of trade costs that run roughly 1.4× higher than coastal economies and an export mix still dominated by unprocessed commodities. That penalty is not merely a trade statistic; it’s a fiscal and human-capital statistic. When customs receipts and export-linked revenues slip, ministries triage, and education budgets are first in line for quiet cuts or deferrals. A transparent back-of-the-envelope shows the stakes: in an LLDC where exports equal 25% of GDP, a shock that trims export volumes by 5% implies a 1.25% GDP hit; if education outlays stand at 4% of GDP and allocations move pro rata, that’s a 0.05%-of-GDP squeeze—$50 million per $100 billion economy—before multiplier and distributional effects. Method note: this is a stylised calculation that assumes proportional fiscal pass-through and no countercyclical borrowing; it is intended to signal order of magnitude, not predict a budget line. Education planners in LLDCs need risk-weighted, region-first market strategies and donor mechanisms that explicitly anchor learning continuity during tariff-driven downturns.

Designing ‘Diversification-Ready’ Education

First, adjust what we teach. The skills bundle for the next five years is more regulatory and logistical than many curricula admit. Students in business and engineering should learn how tariff schedules, safeguard clauses, and countervailing measures alter bill-of-materials choices and supplier networks. Case-based teaching should integrate sectoral examples that illustrate how tariffs of 25–100% on EVs, batteries, solar modules, and critical minerals ripple through local labor markets and impact internship prospects. Short form: graduates need to read a customs schedule the way they read a balance sheet. One practical move is a one-semester “Trade Operations for Educators and Administrators” module that trains district procurement officers and university finance teams to hedge textbook, lab-equipment, and IT purchases when tariff announcements signal price spikes.

Second, protect how we finance learning. Policy unpredictability demands new budget hygiene. Education ministries and large districts should publish tariff-stress appendices in their annual financial plans, analogous to interest-rate sensitivity tables. A simple, transparent approach works: identify top ten import-sensitive categories in your procurement basket (e.g., devices, lab reagents, solar panels for campus microgrids), flag their country-of-origin exposure, and map plausible tariff bands using official announcements and four-year review notices. A procurement calendar that moves device refreshes forward a quarter, or staggers reagent orders through regional distributors, can save 5–10% in a volatile year—money that buys staff time and student support when households are hit by inflation. Even U.S. government filings acknowledge that tariff actions reduce China-sourced imports and increase alternate sourcing; anticipating that shift in purchase planning is a budgetary moat, not a political statement.

Third, widen where we partner. Trade diversion rewrites the map of ‘natural’ academic collaborations. If firms in your region are re-anchoring supply chains to ASEAN or the EU, your institution should be securing faculty exchanges, dual degrees, and joint labs in those markets. China’s push to deepen ties with BRI economies and the EU’s own tariff responses on EVs create both friction and fertile ground for applied research on standards harmonization, low-carbon logistics, and digital customs. For teacher education, this opens a path to embed contemporary trade civics into social studies: students should learn not only what tariffs are but also how they affect the price of their school lunch, the sourcing of their laptops, and the job mix in their towns. Trade policy belongs in civics because it is now a kitchen-table subject.

Fourth, plan for the counter-argument. Advocates of aggressive tariffs will say that domestic production gains can fund schools and expand apprenticeships. Sometimes they will: near-shoring can lift payrolls and local tax bases. But the record so far suggests the substitution is partial and slow. Analyses of prior rounds found limited domestic replacement, with overall U.S. trade deficits widening even as bilateral gaps with China narrowed. That is not an ideological claim; it is an accounting claim, and it means educators should not bank on tariff-induced manufacturing booms to close budget gaps in the near term. The wiser bet is to design dual-use programs that serve local firms when reshoring happens—while also placing graduates in third-market supply chains when it does not. A diversified placement strategy for students is the labor-market analog to diversified export markets for firms.

Finally, anchor the politics to practical steps. The U.S. instrument panel will keep blinking—new Section 301 line items, four-year reviews, sector-specific surcharges. Europe and China will respond to EVs and green-tech inputs; others will follow. Waiting for stability is not a strategy. The strategy is to institutionalize a rapid-response posture: a standing, cross-functional “trade watch” inside education departments and major university systems that translates tariff news into procurement guidance, syllabus updates, and internship placement advisories within thirty days. That is not overreach; it is governance for an era when customs schedules shape classroom reality.

We can name, measure, and teach this shift. Our hook was Canada’s ten-point swing away from the U.S. in a single year; our close is the corollary: everyone is diversifying, but not from the same starting line or with the same tools. China can pivot because it spent years building options; Canada can bend, not break, because supply chains and standards keep it bound to the U.S.; LLDCs face harsher math and need help to keep classrooms open during shocks. The call to action is simple and sober. Build diversification into the bones of education: in syllabi that teach students to read a tariff table; in budgets that hedge against policy whiplash; in partnerships that track the corridors where trade is actually going. Trade diversion is not a footnote to macroeconomics. It is the syllabus for how we will fund, staff, and teach over the next decade.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

China Briefing. (2025, September 1). US-China tariff rates—what are they now?

Kawasaki, K. (2025, September 15). Economic impact of U.S. tariff hikes: Significance of trade diversion effects. VoxEU (CEPR).

Mukherjee, P. (2025, July 9). Canadian companies diversify trade during U.S. tariff war but experts see limits. Reuters.

S&P Global Commodity Insights. (2025, March 10). Interactive: China diversifies trade partners to mitigate U.S. tariff impact.

UNCTAD. (2025, September 1). Uncertainty is the new tariff, costing global trade and hurting developing economies.

UNDP. (2025, August 4). New trade uncertainties amid rising global tariffs call for broader economic diversification in LLDCs.

U.S. Trade Representative. (2024, September 13). USTR finalizes action on China tariffs following statutory four-year review.

U.S. Trade Representative. (2024, December 11). USTR increases tariffs under Section 301 on tungsten products, wafers, and polysilicon, concluding the statutory four-year review.

White & Case LLP. (2024, September 17). United States finalizes Section 301 tariff increases on imports from China.

Warden, S. (2025, September 18). China seeks trade diversification as the U.S. doubles down on protectionism. CZApp.

Comment