The Case for “Designed Stress”: Why Later, Flexible Retirement Can Add Years to Life

Input

Modified

Eustress—purposeful, controllable challenge—appears to extend healthspan Evidence from royal lifespans and modern biology suggests agency under load, not early exit, supports longevity Replace hard retirement cutoffs with flexible, late-career roles that maximize autonomy, mentoring, and recovery

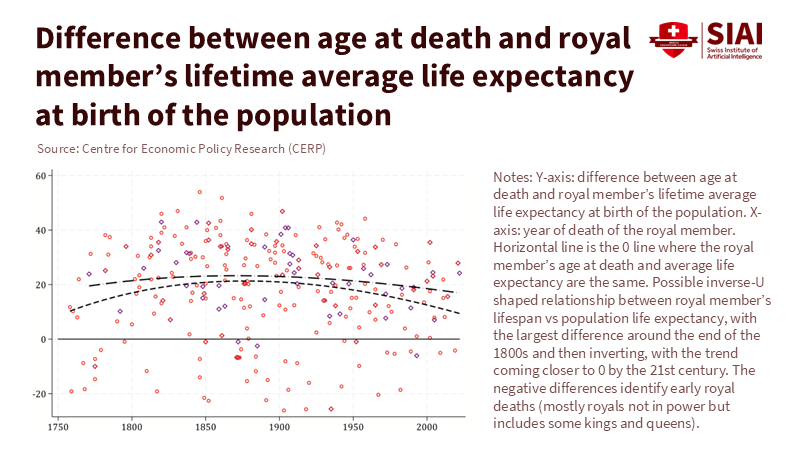

In the 18th and 19th centuries, European royals typically lived 20 to 30 years longer than their subjects. Although that gap has narrowed due to improved public health, one interesting advantage remains: kings and queens often outlive their siblings and partners, even with similar privileges and healthcare. The main reason isn’t better doctors but a different type of stress. The crown brings a sense of purpose and control. This creates “eustress,” a term coined by endocrinologist Hans Selye, which refers to positive and manageable stress that sharpens rather than erodes a person’s well-being. Recent historical research tracking royal lifespans from 1669 to 2022 shows that the extra years for monarchs continue, even as life expectancy for everyone else rises. This highlights the need to distinguish between harmful stress and healthy challenges. Suppose eustress contributes to a longer life for rulers. In that case, our retirement policies should ask a bold question: how can we create late-career work that provides the same motivating stress, especially for teachers, administrators, and the millions ready to leave the workforce?

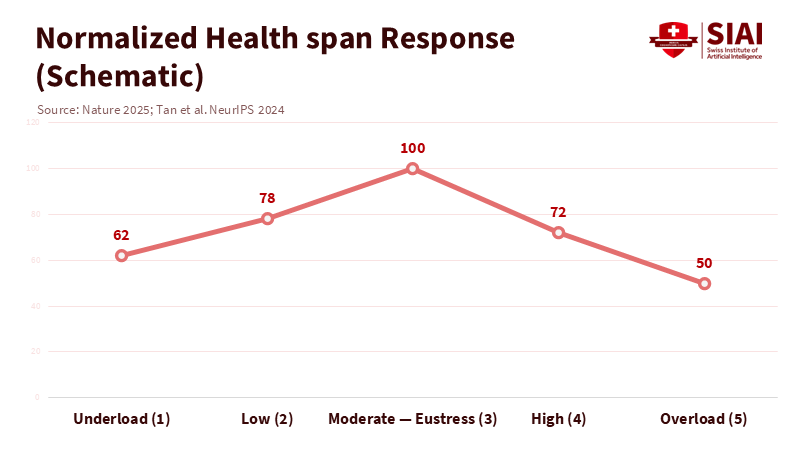

We can reframe the discussion: the goal isn’t to eliminate retirement or idealize work, but to move from a fixed retirement age to “eustress by design.” This means creating jobs that offer autonomy, meaningful responsibilities, and built-in recovery time. The science supports this approach. Years of research in psychology and aging show a Goldilocks curve: a term used to describe the ideal level of stress or challenge for optimal performance. Too little challenge leads to atrophy, too much can crush a person, but the right amount—where the stakes feel real yet manageable—improves health, boosts the immune system, and supports cognitive function. In policy terms, late-career work should fall within this sweet spot. Recent evidence indicates that healthy aging is rising in many wealthy countries, suggesting that many individuals in their late sixties and early seventies can work—if jobs are designed to be meaningful, flexible, and humane.

From Royal Courts to Ordinary Classrooms

The lesson from royalty applies to everyday life because it distinguishes between purpose and wealth. While royals had status from birth, only monarchs held significant responsibility. This responsibility likely created eustress—challenges that foster personal agency—which in turn translates to a longer life. The analysis reveals that the “royal advantage” refers to the longevity enjoyed by monarchs, which peaked in the 1800s, shrinking as sanitation and vaccines improved health for everyone; however, the longevity benefit for rulers within their families remains. This aligns with modern psychology: eustress occurs when demands match an individual's abilities and they feel in control, thereby boosting engagement and resilience. For educators and school leaders, this concept is familiar: the right amount of challenge in a classroom leads to mastery; in one’s career, it seems to buffer against aging. Therefore, policy should consider personal agency—not just income or access to healthcare—as a factor in health.

The biology supports this social narrative. Recent reviews in Cell Metabolism and similar journals argue that mild, intermittent stressors—like cognitive challenges, physical activity, temperature variations, and even fasting—trigger repair mechanisms that protect both the brain and body. These signals, including AMPK, sirtuins, and heat-shock proteins, improve mitochondrial function and adaptability. Notably, “healing stress” requires time for recovery. In designing jobs, this means allowing control over pace, enabling variations in intensity, and ensuring time for restoration. When late-career roles provide this structure, the health benefits resemble public policy rather than royal privilege.

What the Biology Says: The Goldilocks of Stress

The education sector already generates eustress. Teaching is often demanding cognitively and socially, but at its best, it provides clarity of mission, daily feedback, and a strong sense of control—conditions that fall within the “challenge with agency” zone. This doesn’t ignore the issue of burnout; instead, it highlights that the boundary between harmful stress and healthy stress can shift. Purpose serves as a known protective factor for older adults, linked to better functioning and lower mortality risk, even when factoring in socioeconomic status. If purpose helps manage stress, and good work nurtures purpose, then policies that keep older professionals engaged (with appropriate safeguards) can plausibly extend their healthspan. This idea aligns with evidence showing that each additional year of schooling reduces adult mortality by about 2% across 59 countries—an effect likely influenced by both resources and the cognitive-social benefits of ongoing challenges. By emphasizing the role of purpose in managing stress, we can empower older professionals to take control of their health and well-being.

The broader context is also changing in our favor. The IMF’s 2025 World Economic Outlook notes measurable improvements in the cognitive and physical abilities of those over 50. This suggests that older workers can contribute to a more adequate labor supply if policies are adjusted. In other words, “70 is not what it used to be” for the average person, although disparities still exist. The main takeaway is practical: a growing number of workers in their late sixties can participate in meaningful, intellectually stimulating work if jobs are redesigned to reduce physical burdens and increase autonomy and mentorship. The challenge lies not in biology but in institutions that still assume a sharp drop-off at 65. However, with the potential for policy change, we can look forward to a future where late-career roles are designed to promote eustress and longevity.

Designing Retirement for Eustress, Not Exhaustion

Research on retirement timing and mortality produces mixed results, underscoring the importance of thoughtful design. A recent study examining Spain’s 1967 pension reform found that delaying retirement increases mortality between the ages of 75 and 85, with no significant impact earlier. Other research indicates health improvements associated with retirement in physically demanding jobs. Yet, more studies link early retirement to higher mortality, often due to selection bias and the loss of structure. The common theme is variability: it’s not simply “working longer” that helps or hurts, but rather the type of work, the conditions, and the individuals involved. A fixed retirement age cannot capture this complexity. Our policy decision is between a rough cut-off or a system that customizes late-career roles to deliver eustress—control, meaning, and recovery—while minimizing chronic stress. By stressing the need for a nuanced approach to retirement, we can encourage policymakers to consider the individual circumstances and needs of older workers.

Concrete steps can be taken in schools and universities to address this issue. First, create “encore” roles that turn implicit knowledge into lasting institutional memory: master-teacher residencies, curriculum development teams, and clinical coaching positions. Such roles are highly demanding cognitively and socially, while being low on repetitive stress, and can easily fit into phased schedules. Second, develop formal phased-retirement tracks—two- or three-year gradual transitions that reduce contact hours while increasing mentoring and content creation—so older staff members maintain levels of engagement and control without the burden of constant pressure. Third, redesign evaluations to focus on contribution portfolios rather than time spent in a seat. By emphasizing mentoring outcomes, capstone projects, or course redesign efforts, institutions encourage autonomy over compliance. These changes are not mere add-ons; they act as health interventions disguised as human resources policies, shifting late-career stress toward the eustress range favored by biology.

Fourth, combine job design with recovery strategies. The same research that highlights the benefits of mild stress also warns against constant pressure. Late-career contracts should ensure predictable downtime throughout the year, including mini-sabbaticals for focused projects. This approach doesn’t harm productivity; instead, it reallocates it by aligning intense work periods with necessary reflection, which is essential for expert performance. Fifth, invest in cognitive support systems that maintain challenge while managing risk of failure: teaching assistants for large classes, instructional design help, and modern technology to reduce decision fatigue. Eustress requires challenges, but it also necessitates systems that transform uncertainty into learning, rather than anxiety.

We need to address equity as well. The cognitive resources that enable late-career eustress aren’t evenly distributed. Individuals in physically demanding or low-control jobs often gain less from working longer and may even suffer. This isn’t a call for universal early retirement; it’s a request for varied paths. Policy can safeguard health by allowing earlier exits for workers in high-stress roles while actively recruiting late-career educators, researchers, and administrators into redesigned positions. At the systemic level, the European Commission’s 2024 Ageing Report and new guidelines on flexible retirement highlight the economic need to extend working lives and also indicate significant disparities by education and job type—areas where targeted institutional action can make a difference.

We should consider the main criticisms. First, there’s the healthy-worker effect: perhaps those who feel purposeful work longer and tend to live longer. That’s true, but the royal data avoids this selection bias—rulers are not self-selected achievers—and biological studies provide mechanisms that policy can replicate: agency, challenge, and recovery. Second, the risk of burnout: late-career teachers may already feel overstretched. That’s why the proposal doesn’t suggest “work more,” but rather “work differently,” with more autonomy and manageable control levels. Third, critics argue that institutions can’t afford customized paths. The counterargument is actuarial: extending engaged service by even two to three years among experienced staff, while improving health outcomes that lower long-term costs, is cheaper than frequent turnover and the hidden costs of institutional forgetting.

Finally, let’s think about the broader impacts. Education serves as a key source of eustress in society. A 2024 global meta-analysis in The Lancet Public Health estimates a 2% reduction in adult mortality for every additional year of schooling; long careers in education double that effect—both through teaching and by exemplifying meaningful engagement. Additionally, macro research from the IMF suggests that healthier aging will boost the adequate labor supply among older groups through 2100, if job designs evolve. The policy choices we make today, focusing on late-career structures that prioritize purpose and control, will either increase these benefits or waste them. The decision is not between retirement and work, but somewhat between distress and eustress.

Here is the call to action. Take the royal example seriously: longevity follows purpose when the burden is manageable. Replace a steep retirement cliff with gradual, flexible pathways that maintain real challenges, high control, and necessary recovery. Use encore roles to transform teaching into a resource for mentorship, and adjust evaluations to emphasize contribution portfolios that acknowledge design, mentorship, and institutional stewardship. Embed these changes into contracts and budgets, not temporary programs. Then track what matters: late-career retention, mentoring hours provided, burnout and recovery statistics, and—over time—health outcomes. If we organize job roles around the biology of eustress, “working longer” will shift from a catchy phrase to a compassionate longevity policy. Our graduates deserve institutions that have long memories; our teachers deserve careers that extend their lives; and our aging societies deserve a job market that values purpose as a public health resource. The secret to longevity among royals is not the palace. It is personal agency under a manageable load. Let’s build that into the work we do.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

American Psychological Association. “Distress vs Eustress: Critical Thinking Exercise.” APA TOPSS resource (accessed 2025).

Batinti, A., Costa-i-Font, J., & Shanda, V. “The long life spans of royals reveal the secret of ‘healthy stress’.” VoxEU/CEPR, 16 Sept 2025.

Belles-Obrero, C., Jiménez-Martín, S., & Ye, H. “The Effect of Removing Early Retirement on Mortality.” FEDEA Working Paper, May 2024.

Calabrese, E. J. “Hormesis determines lifespan.” Biogerontology, 2024.

International Monetary Fund. World Economic Outlook, April 2025: Chapter 2 — The Rise of the Silver Economy and Online Annex. IMF, 2025.

Lancet Public Health (Balaj, M., et al.). “Effects of education on adult mortality: a global systematic review and meta-analysis,” 2024.

Mattson, M. P. “The hormesis principle of neuroplasticity and neuroprotection.” Cell Metabolism, 2024.

OECD. Flexible Retirement Pathways. European Commission, 2025.

PositivePsychology.com. “What Is Eustress? A Look at the Psychology and Benefits,” accessed 2025.

Teques, A. P., et al. “Well-being and Retirement in Europe: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis,” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 2025.

Comment