The Private Engine of China’s Green Transition

Input

Modified

China’s green transition is driven by private equity, not state subsidies This market-led buildout cuts costs, lowers geopolitical risk, and is nudging emissions down Europe should use compliant Chinese solar and storage now while scaling its own niches and grids

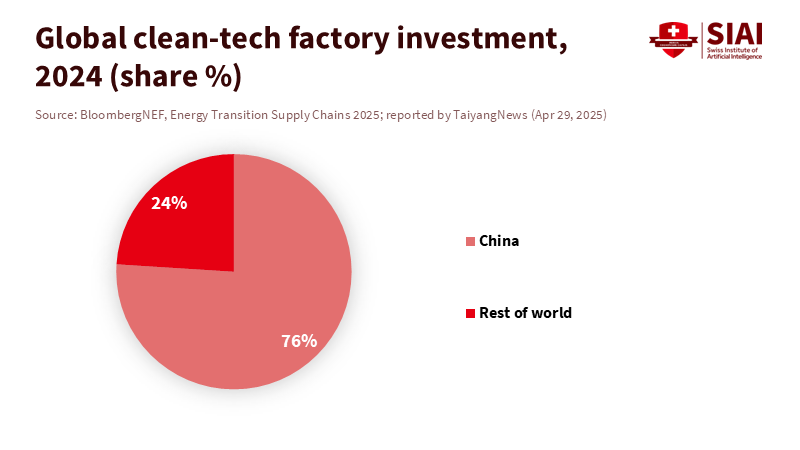

If there’s one number that encapsulates the global energy landscape in 2025, it’s 76. This was China’s share of all clean-tech factory investments announced worldwide in 2024. The investments spanned batteries, solar, wind components, and electric vehicles, all from firms raising and risking equity, not through government loans. China’s carbon dioxide emissions fell by about 1% over the last year, even as electricity demand grew. New capacity came online swiftly; prices for key technologies dropped; exports surged. This resulted in a Chinese green transition that appears more like a private capital race to scale rather than a state-subsidy project. This change is significant. Equity capital is quicker, more adaptable, and less tied to geopolitical issues than debt-driven efforts. If this trend continues, Europe’s climate calculations will also shift. Cheaper Chinese panels and batteries are not a hurdle for decarbonization; they serve as a bridge to it, especially for energy-strained southern member states.

The private engine behind the Chinese green transition

The main change is who takes on the risk. National purchase subsidies for new-energy vehicles ended in 2022, replaced by limited tax relief. However, investment picked up speed. Public markets, retained earnings, and venture capital financed growth across the supply chain. BloombergNEF reports over $2 trillion in global energy transition spending in 2024, with China as the largest single market. Battery leader CATL is expected to maintain annual capital spending between RMB 31–34 billion through 2025. In solar, Chinese factories account for over 80% of global manufacturing capacity, with the upstream share nearing 95% based on plants under construction. Equity-backed growth has pushed global cell prices down to about $0.12/W at certain points in 2024, lowering costs across entire project pipelines. This isn’t a story about subsidies; it’s a story about balance sheets, where the financial health and stability of these companies play a crucial role in driving the green transition.

Speed is the second key point. China installed a record 235 GW of solar in 2023, more than doubling its figure from 2022, while the market share for electric cars approached the mid-40s in 2024. Including wind, storage, and nuclear, the country has at times reduced coal’s monthly share of power to historic lows. These results align with an equity-driven build-out: a strategy where private firms grow where margins and market access are available; they adjust when they aren’t. This approach, which is primarily driven by equity investment, allows for quick adaptation and growth in areas where it is most profitable. LSE’s new database on overseas green manufacturing investment reveals more than $220 billion in commitments by Chinese firms since 2022, covering over 50 countries. This is Chinese capital supporting global decarbonization, not binding host nations to public debt agreements.

An equity-led Chinese green transition cuts geopolitical risk

Why does the ownership structure matter for geopolitics? Loan-based programs can tie borrowers to a state lender and its foreign policy. Equity investment spreads risk to the firm and its shareholders. If a project fails, creditors do not pursue a government. If a market closes, the firm can relocate production or reduce its capital investment. The new wave of Chinese green foreign direct investment (FDI) is primarily corporate and equity-heavy. Even observers in East Asia who were once skeptical now note three trends: private firms are in charge; equity is the main tool; and decarbonization products, not strategic ports, define the portfolio. This mix weakens the common “debt-trap” critique and lowers the chances that a climate project becomes a geopolitical pawn.

The emissions trend strengthens this argument. Carbon Brief’s high-frequency analysis shows China’s CO₂ emissions falling roughly 1% year-on-year in the first half of 2025, with declines starting in March 2024 and persisting as new clean capacity replaced coal. None of this suggests a straightforward path; coal approvals rose again in early 2025, and grid bottlenecks are still a challenge. However, the overall direction is telling. When private capital drives the Chinese green transition, production increases where costs are lowest and learning curves are steepest. This supply dynamic reduces the cost of decarbonization globally and challenges claims that China’s climate progress relies solely on state support.

Europe’s energy math and the Chinese green transition

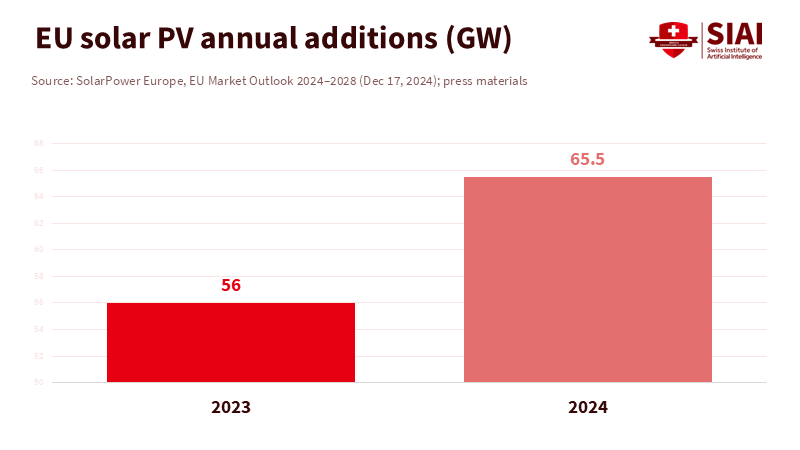

Europe’s goals are clear: a binding 2030 renewables share of at least 42.5%, with ambitions to reach 45%. Solar additions reached another record in 2024, with around 66 GW, but momentum has slowed in 2025 as rooftop incentives were cut in several member states. Forecasts now indicate the first annual slowdown in a decade. This makes module price and supply even more critical. Southern Europe particularly needs volume at the lowest cost to lower retail prices, reduce energy poverty, and shift daytime loads off gas. Chinese panels can meet that demand now. The bloc also wants to rebuild a domestic solar industry. It should, but achieving climate targets requires both industrial policy and open supply chains in the short term.

Trade policy should respond to the physics of climate, not the politics of rivalry. The EU’s firm countervailing duties on Chinese electric vehicles address a specific subsidy issue. Solar is different. Europe’s own industry group warns that broad trade defense measures for PV would raise costs, slow down deployments, and worsen the gap for 2030. A practical approach is to maintain solar imports to meet targets while providing targeted, short-term support for bottlenecks—such as glass, wafers, and inverters— where Europe can be competitive. It’s essential to expedite grid development and flexibility so that low-cost solar can lower bills in the south and drive industry in the north. In brief, maintaining open trade is crucial to not view the Chinese green transition as a threat to Europe’s climate plans; but rather, consider it the market advantage it is.

Policy steps to work with the Chinese green transition

First, in procurement. Public buyers and regulated utilities, who are significant players in the energy market, should use total-system cost metrics that consider declining module, battery, and inverter prices. In energy-poor regions, priority should be given to ready-to-go solar and storage projects that can clear auction queues in 12–18 months. Employ quality and sustainability criteria that are tough on forced labor and waste, but neutral on country of origin, so the cheapest compliant products succeed. This approach leverages the cost savings generated by the Chinese green transition while enforcing Europe’s standards.

Second, with industrial policy. Europe’s manufacturing revival will rely on clear targets and focused support. The EU’s roadmap outlines 30 GW of domestic solar manufacturing capacity by 2030 across the value chain. To achieve this, co-finance only where a path to cost parity exists and where European firms have strong positions. Avoid blanket tariffs that would drive up costs for every school and hospital rooftop. Instead, use time-bound grants, reduce risks for first-of-a-kind plants, and offer low-cost power contracts for energy-intensive stages like ingots and wafers. Keep the possibility open for joint ventures with Chinese firms that contribute process knowledge in exchange for local jobs and reciprocal market access.

Third, in finance and research. Universities and vocational institutes should adjust their curricula to focus on grid integration, power electronics, and battery management. The job market is here now. Fund collaborative labs that test modules and batteries from multiple suppliers under identical conditions. Ensure transparency in tracking technology performance and failure rates. For policymakers, use the latest market data to time support effectively. BloombergNEF notes that China captured most clean-tech manufacturing investment in 2024; the key lesson is not to mimic China’s subsidy model, but to leverage Europe’s advantages and buy the cheapest imports. Where imports lower the cost of climate action today, embrace them. Where Europe can excel in the future, invest.

Anticipate the criticism. Detractors will argue that Chinese firms still gain from state support, claiming that “equity-led” is just a facade. It is true that tax breaks, land policy, and credit conditions are significant. The question for Europe isn’t whether China’s policies exist, but whether Europe can meet its climate goals without today’s lowest-cost inputs. In solar, excluding Chinese supplies would slow installations and increase costs, as Europe’s industry itself cautions. Others may claim that depending on foreign supplies poses a security risk. The solution lies in designing a diverse portfolio: vary suppliers, maintain strategic reserves of crucial components, and standardize interfaces for easy replacements. Over-securitizing the supply chain may lead to a slower and costlier transition. In contrast, adopting smart resilience is straightforward and feasible within current budgets.

The simplest and most crucial message is this: private capital has become the driving force behind the Chinese green transition. It has accelerated factory scaling, cut unit costs, and—importantly—begun to change China’s emissions trend. This capital is not without risk or political implications, but it is less likely to trap partners in debt or stall during geopolitical tensions. Europe faces a pressing deadline for 2030 and a slowing rooftop market. It can opt for higher prices, fewer projects, and missed targets, or it can leverage the scaling effects created by China’s private build-out while enforcing high standards and rebuilding competitive sectors at home. The practical path is clear. Keep trade channels open for compliant, low-cost solar, storage, and EV components; expedite grid upgrades; focus industrial policy where Europe can succeed; and train the technicians needed to connect everything. Let the numbers guide the decision. The world needs the most affordable clean energy now, not the ideal industrial policy later. The equity-led Chinese green transition is providing it. Europe should take advantage of this for its citizens.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

BloombergNEF. (2025, January 30). Global Investment in the Energy Transition Exceeded $2 Trillion for the First Time in 2024.

BloombergNEF. (2025, April 28). Energy Transition Supply Chains 2025: China dominates clean-tech manufacturing investment.

Carbon Brief. (2025, May 15). Clean energy just put China’s CO₂ emissions into reverse for the first time.

Carbon Brief. (2025, August 21). Record solar growth keeps China’s CO₂ falling in first half of 2025.

East Asia Forum. (2025, October 20). Chinese firms chip in on climate action.

International Energy Agency (IEA). (2024). Global EV Outlook 2024.

International Energy Agency (IEA). (2025). Global EV Outlook 2025.

IEA. (2025). China’s share in global PV manufacturing capacity, 2024 and 2030.

IEA. (n.d.). Solar PV Global Supply Chains — Executive summary.

IEA-PVPS. (2024). Snapshot of Global PV Markets 2024.

National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL). (2025, February 4). Winter 2025 Solar Industry Update.

Reuters. (2021, December 31). China to withdraw NEV purchase subsidies at end-2022.

Reuters. (2023, June 21). China extends NEV purchase-tax exemption to 2027.

SolarPower Europe. (2024, December 17). EU Market Outlook for Solar Power 2024–2028.

SolarPower Europe. (n.d.). Statement opposing trade defence measures on solar PV products.

SolarPower Europe. (n.d.). #MakeSolarEU — 30 GW European manufacturing by 2030.

European Commission. (2025). REPowerEU — Three years on.

European Commission. (2024, December 12). Definitive countervailing duties on BEVs from China.