Proposing an Education Agenda for Democratic Resilience: when Facts Don’t Move Votes

Confidence follows identity more than facts Schools should teach election procedures and prebunk manipulation Local transparency and routine audits build resilience when results disappoint

The most telling number from the

China's Reserve-Currency Test Will Be Won, or Lost, on Stablecoins

Stablecoins are the battleground for China’s reserve-currency bid Without a trusted RMB token, dollar stablecoins entrench dominance and siphon savings Use Hong Kong and mBridge to launch audited RMB rails for trade and tuition

When Algorithms Wobble: AI, Information Cascades, and the New Bank-Run Curriculum

When Algorithms Wobble: AI, Information Cascades, and the New Bank-Run Curriculum

Published

Modified

AI accelerates information cascades, turning rumors into rapid bank runs Stability now hinges on dampening synchronized behavior, not just capital buffers Build rumor-aware stress tests, fast disclosures, and drill-based curricula

The systemic risk issue is not just a concern for supervisors and traders, but also for educators and administrators. This was starkly illustrated when forty-two billion dollars left a single U.S. bank in one trading day last year, with another $100 billion set to go the next morning. This is not a typo; it reflects the new speed of panic. In March 2023, depositors at Silicon Valley Bank withdrew a quarter of the bank's deposits within hours. Management expected more than half of the remaining balance would leave the following day. The bank failed before the line could finish forming. This episode reminded us that modern finance depends on coordination. When many people act together, even a well-built structure can fail. It also highlighted that social media and mobile banking have shortened the time between rumor and collapse. As generative AI speeds up how provocative claims are created, spread, and accepted, the coordination issue at the heart of financial stability becomes an information-systems problem. Educators and administrators play a crucial role in addressing this challenge.

We often use plumbing metaphors to explain systemic risk, such as liquidity pools, transmission channels, and circuit breakers. While those metaphors are helpful, they overlook the role of shared beliefs. When everyone sees the same information and reacts similarly, small shocks can amplify. The reason for action is not just balance-sheet math; it also involves real-time narrative dynamics. By 2025, those dynamics are managed through models—ranking, recommending, summarizing, and increasingly deciding. If the next crisis moves at the speed of content, then classrooms, newsrooms, compliance desks, and central bank dashboards are all part of the same early-warning system.

A well-known engineering story illustrates this concept. On the morning London opened its Millennium Bridge, it wobbled not because of poor construction but because people adjusted their steps in sync as the deck swayed. Each person's slight movement made it more likely the next person would adapt too. After reaching a certain point, the crowd and the bridge created a feedback loop. Engineers fixed the issue by adding dampers, not by retraining pedestrians. Finance has similar thresholds and feedback. While dampers exist—like deposit insurance, lender-of-last-resort, and stress tests—the crowd's rhythm has changed.

From Wobbly Bridges to Wobbly Balance Sheets

The bridge analogy highlights two truths about coordination. First, vulnerability can exist even when design standards are met. Second, thresholds are significant. With enough walkers, or similarly positioned investors, the system can tip into a different state. The Diamond-Dybvig theory formalized this in banking: multiple equilibria allow for a self-fulfilling run to happen even when fundamentals are solid. In the 2023 run episodes, the change was not just due to interest-rate risk on bank balance sheets; it was also a result of the density and speed of shared information that led depositors to the same conclusion simultaneously. This is why uninsured concentrations were so critical: at year-end 2022, about 88 to 94 percent of SVB's deposits exceeded the insurance limit, and those accounts could—and did—move together in large amounts.

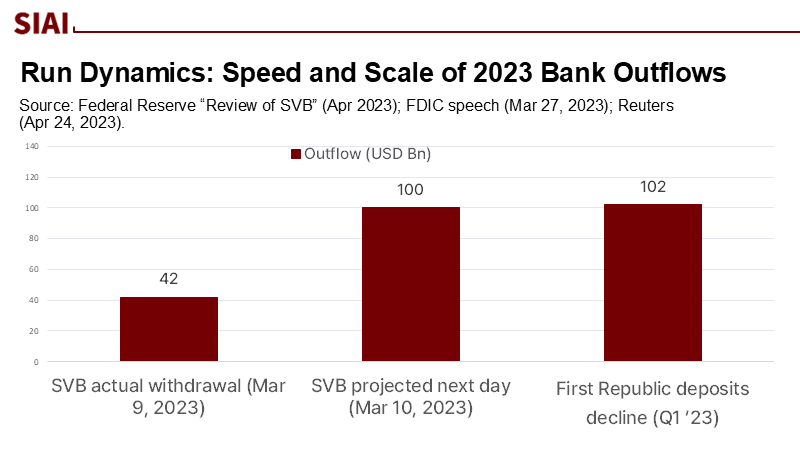

Speed is now crucial. The Federal Reserve's review recorded more than $40 billion leaving on March 9 alone, with over $100 billion expected on March 10 if conditions did not change. This is much faster than traditional cases. First Republic then revealed over $100 billion in quarterly outflows, with an estimated $25 to $40 billion departing in single days during peak stress. Coordinated messaging among concentrated depositor networks clearly played a role. This is what the bridge taught us: small, rational individual actions, synchronized by feedback, create forces the structure wasn't built to withstand. Dampers must evolve as well.

AI Turns Rumors into Runs

Two developments since 2023 have strengthened the connection between rumor and withdrawal. The first is empirical: social media activity is associated with increased distress. A multi-author study using extensive Twitter (X) data shows that banks with higher pre-existing exposure on social media experienced larger losses during the run, even when controlling for uninsured deposits and unrealized bond losses. In hourly data, tweet volume about specific banks aligns with stock-price declines, indicating that attention itself amplifies vulnerability. The second is structural: AI changes how attention is produced. It reduces the cost of creating plausible claims at scale and increases the likelihood that many users will simultaneously see and act on the same narrative.

Caution is warranted in interpreting the figures. We now have early signs on the deposit side, not just prices. A UK study, reported in February 2025, indicated that AI-generated fake content about a bank's health notably increased respondents' intentions to transfer funds to the bank. The researchers estimated that, in some cases, a £10 social ad spend could influence up to £1 million in deposits. These figures, however, depend on context and design. Suppose a small budget can create a widely shared clip that trends for an hour. In that case, a local bank with a concentrated corporate clientele may face large synchronized outflows, forcing emergency liquidity measures. A simple calculation illustrates this: for a mid-size bank with $12 billion in deposits and 50 percent uninsured, a 2 percent shift among uninsured accounts equals $120 million. This is enough to trigger negative headlines, collateral haircuts, and more withdrawals. The narrative can drive causal connections.

Supervisors have taken notice. The BIS's 2024 Annual Economic Report warns that AI can both improve and threaten financial stability—enhancing monitoring while raising the risk that multiple actors take similar actions or act on shared model errors. The Financial Stability Board's 2024 assessment also highlights the concentration in standard AI tools and data, new channels for misinformation, and the need to improve supervisory capabilities. In the UK, the Bank of England has discussed the inclusion of AI risks in its annual stress tests and emphasized the need for governance that accounts for interactions among models. The trend is clear. We are transitioning from unique risks to system-level similarity risks—what engineers refer to as modes of vibration.

A reasonable critique counters that digitalization alone does not cause deposit volatility in regular times. The ECB's recent paper finds that mobile app availability and regular online use don't raise outflow volatility across the euro area by themselves; social media amplification mainly matters in specific stress events. This nuance is crucial. It shows that the risk is not "technology" itself, but rather technology interacting with shared exposure (uninsured deposits), unclear news, and time-compressed coordination. In other words, the bridge does not wobble every day. It sways when many pedestrians adjust together near a threshold—and when there are no dampers to manage the sway.

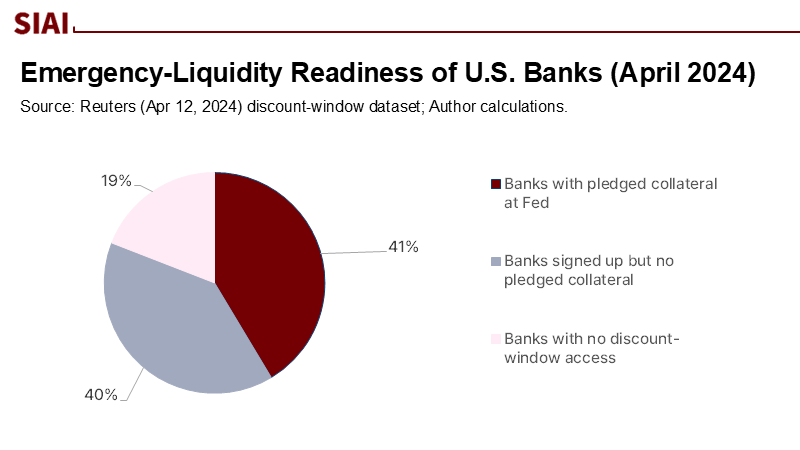

What We Teach Now Determines What Fails Next

If the coordination problem has shifted into the information landscape, the education agenda needs to adjust. Finance and public policy courses should include "information-cascade drills" alongside liquidity-coverage math. In practical terms, schools and training programs can run live simulations where students act as depositors, treasury teams, risk officers, journalists, and supervisors reacting to a sudden (synthetic) AI-generated rumor about a regional bank. The exercise should incorporate time-stamped social posts, changing search results, and models showing core funding loss linked to rumor intensity. It should also require decision-makers to rehearse emergency liquidity mechanics: positioning collateral, daylight overdraft use, and access to discount windows. One concerning data point: a year after SVB's collapse, less than half of U.S. banks and credit unions had established the legal authority to borrow from the Federal Reserve's discount window during emergencies—indicating a readiness gap now under consideration for reform. If graduates cannot execute these steps under pressure, their employers will struggle when every minute counts.

For supervisors and central banks, the lesson is to add dampers to the information system, not just the balance sheet. The policy discussions already reflect this direction. SUERF authors have suggested that authorities build expertise in AI, establish "AI-to-AI links" to allow supervisory tools to analyze and react to model-driven activity in real-time, and create "triggered facilities" that activate when monitoring signals exceed certain thresholds. The FSB recommends closing data gaps on firms' AI usage, tracking concentration in models and providers, and considering misinformation risks in stability frameworks. Specifically, stress tests should integrate rumor-shock modules that combine deposit flight patterns with content-spreading dynamics. Communication protocols should require banks to publish rapid and verifiable dashboards—detailing liquidity coverage, collateral held at central banks, and deposit mix—alongside pre-approved messaging that can go out within minutes, not hours. These are dampers to counteract the narrative swings that now drive withdrawals.

The private sector also has its tasks. Treasury and communications teams should work together on early-warning signals from public feeds. This includes tracking unusually fast correlations between negative terms and the bank's name, spikes in short-horizon retweet networks, and sudden changes in search-query patterns. The evidence from Cookson et al. indicates that such attention measures contain information on an hourly basis during crises. Institutions must also learn how to respond to issues of content authenticity. While stronger provenance signals will help until watermarking and cryptographic verification become standard, it is critical to train staff to debunk quickly with relevant information. A brief method note can guide decisions: estimate your bank's one-hour runoff elasticity to a 1-sigma spike in social media attention based on past incidents; establish a "go-public" trigger that balances the risks of triggering panic against the benefits of preventing it. When that trigger activates, release easy-to-check metrics—such as available central bank capacity, cash on hand, and ratios of insured to uninsured deposits—along with links to third-party validation when possible.

Policymakers should anticipate objections. Someone might argue that rumor-aware stress tests are speculative. Another concern is that "AI-to-AI" supervisory tools may lead to excessive monitoring or moral hazards. A third might fear that this approach could stifle free speech. The correct response is not to suppress content; it is to build resilience against cascades. The ECB's findings support this: technology is not destiny. We can lower thresholds by diversifying deposit bases, capping correlated exposures, and proactively committing to transparent emergency liquidity access. We can add dampers by speeding up supervisory communications and practicing them publicly. We can also slow the most hazardous feedback loops, for example, by considering time-limited withdrawal controls on large, fast corporate transfers when a bank has high liquidity coverage at the central bank, paired with real-time disclosures and strict safeguards. Think of this as temporary control for a swaying bridge while the dampers take effect, not a permanent obstacle.

Educators have a crucial role in this redesign. The next generation of risk managers and policy analysts should be skilled in both cash-flow math and attention dynamics. A capstone course may require students to create a simple rumor-to-run model using publicly available data. They would estimate its parameters from past events (such as tweet volume, search trends, and price gaps) and then propose a communications and liquidity strategy, which would be tested in a timed simulation. The goal is not to produce a perfect forecast; it is to enable disciplined action under uncertainty. If schools offer this training, agencies will seek out graduates, and banks will adopt it. The result is a system that views information friction as a key component of financial plumbing rather than an afterthought added to press releases.

Return to that 24-hour window in March 2023: $42 billion out, and another $100 billion lined up. The noteworthy point is not just the amounts; it is the coordination. AI will not alter the human inclination to act in unison, but it will make synchronized actions easier to initiate, faster to spread, and more challenging to reverse. That is why the next generation of dampers cannot rely solely on capital and collateral. They must also include rapid, credible disclosures; rumor-aware stress design; and hands-on experience with information shocks—in classrooms, drills, and at the very desks where decisions will be made. If we recognize that the system now sways when narratives align, our goal is to lower the threshold of wobble and accelerate the dampers. We need to develop a curriculum that identifies cascading risks as key concerns and invest in supervisory tools that directly engage with models. We should welcome criticism, promote transparency, and practice through challenging situations. If we do this, the next time the crowd starts to move, the bridge will steady faster, and the line at the virtual teller will be shorter.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Bank for International Settlements (2024). Annual Economic Report 2024: Artificial intelligence and the economy—implications for central banks (Ch. III).

Bank of England (2024, June). Financial Stability Report.

Cookson, J. A., Fox, C., Gil-Bazo, J., Imbet, J. F., & Schiller, C. (2023). Social Media as a Bank Run Catalyst. FDIC Working Paper.

Diamond, D. W., & Dybvig, P. (1983). Bank runs, deposit insurance, and liquidity. Journal of Political Economy, 91(3), 401–419. (Classic foundation).

European Central Bank (2025). Wildmann, N. Mind https://www.ecb.europa.eu.

Financial Stability Board (2024). The Financial Stability Implications of Artificial Intelligence. https://www.fsb.org.

Federal Reserve Board, Office of Inspector General (2023). Material Loss Review of Silicon Valley Bank.

Federal Reserve (2023, April). Review of the Federal Reserve’s Supervision and Regulation of Silicon Valley Bank.

FDIC (2023, Mar. 27). Recent Bank Failures and the Federal Regulatory Response (speech).

Reuters (2023, Apr. 24). First Republic Bank deposits tumble more than $100 billion.

Reuters (2025, Feb. 14). AI-generated content raises risks of more bank runs, UK study shows.

Strogatz, S. H., Abrams, D. M., McRobie, A., Eckhardt, B., & Ott, E. (2005). Crowd synchrony on the Millennium Bridge. Nature, 438, 43–44. (See news/summary coverage).

SUERF (2025, May 15). Danielsson, J. How central banks can meet the financial stability challenges arising from artificial intelligence.

The Structural Engineer (2001). Dallard, P., et al. The London Millennium Footbridge (description of synchronous lateral excitation).

Similar Post

A Narrow Channel: East Asia’s Pragmatic Pivot Under Tariff Shock

Tariffs and chip controls are forcing a pragmatic Japan–Korea thaw Ishiba and Lee, both China-leaning, hedge via Beijing while keeping U.S.

When Tariffs Don’t Buy Strength: Why the Dollar Fell, and What the Models Missed

Tariffs in 2025 weakened the dollar instead of strengthening it Markets priced in retaliation, limited U.S.

The Suffocation of “Efficiency”: What Germany’s Red Tape Teaches Education Reform

Germany’s reputation for efficiency hides massive losses from excessive bureaucracy Evidence from trains, bakeries, and schools shows that cutting redundant processes boosts performance and retention.

Tariffs, Talent, and the Stack We Teach: How U.S. Protectionism Is Rewiring Asian Education

Tariffs, Talent, and the Stack We Teach: How U.S. Protectionism Is Rewiring Asian Education

Published

Modified

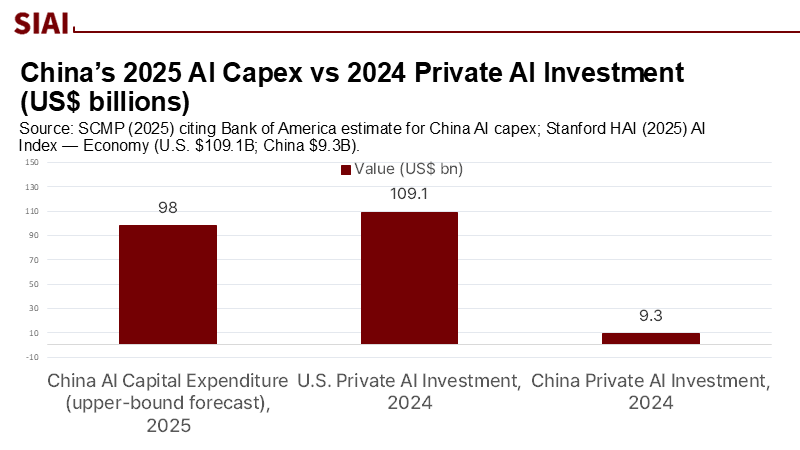

U.S. protectionism is splitting markets and learning tools into rival stacks China’s AI capex and ASEAN infrastructure create a pull toward its stack Answer with block-biliteracy, pooled compute, and portable standards to keep choice

One number captures the urgency of the situation: 15%. This is the tariff level the United States now applies to European imports, and the effective floor many Asian exporters must plan around. The administration's actions, negotiations, and carveouts are shifting week to week, creating a sense of urgency. Prices are responding, plans are stalling, and universities are discovering that tariffs don’t just reprice goods; they segment ecosystems—chips, cloud credits, textbooks, even accreditation. In the same year, China is projected to pour as much as US$98 billion into AI capital spending, underwritten by a new state-backed US$8.2 billion fund. A hard tariff wall on one side; an industrial-policy engine on the other. In classrooms from Bangkok to Bandung, the choice no longer reads “which supplier,” but “which stack.” That is why the tariff story is, at root, an urgent education story.

From price shock to pipeline shock

The conventional take treats tariffs as macro noise that the education sector can ride out. That underestimates the impact of a durable 10–15% tariff regime on the micro-economy of learning. Executive actions in April and July introduced and then modified a “reciprocal” tariff framework, while parallel deals produced a flat 15% rate for EU goods—a signal that Washington is willing to normalize elevated duties, not simply threaten them. Court fights may prune the legal basis, but the policy thrust is plain enough for procurement officers to notice. When the price of imported lab equipment, developer workstations, or cloud credits rises and the legal basis wobbles, multi-year syllabi and infrastructure plans wobble with it. For ministries budgeting around five-year cycles, the result is not a transient price bump but an incentive to switch suppliers, platforms, and standards toward the stack they can reliably access.

The export-control environment compounds that incentive. In January 2025, the U.S. Commerce Department’s Bureau of Industry and Security moved—then partially reversed course in May—toward an unprecedented control on closed-weight AI models and tighter rules on advanced computing items. Even with rescission of the “AI Diffusion” rule framework, much of the emphasis on controlling chips, large clusters, and specific model weights persists, and the mere signal of possible licensing in future rounds is enough to make universities think twice about relying on a single, foreign-hosted stack. The administrative churn is the point: standards and access are now policy variables. Education systems that plan for volatility will favor multi-homed compute, bilateral recognition of credentials, and courseware that ports across ecosystems.

If we reframe tariffs as a pipeline shock, the stakes sharpen. In the 1930s, block economies hoarded commodities; today, they hoard compute, standards, and trust in credentials. A 1–2 percentage-point price shock imposed on AI-relevant imports would be survivable in isolation. But layered atop export controls and procurement uncertainty, it nudges systems toward the nearest reliable platform. However, with proactive policy and procurement strategies, these shocks can be turned into opportunities. That is how trade policy becomes curriculum policy, and how we can shape a more hopeful future for education and AI infrastructure.

China’s AI engine, ASEAN’s gravitational pull—and the Japan–Korea question

Against that policy weather, the supply landscape in Asia is rapidly diverging. China’s AI capital expenditure is forecast between ¥600–700 billion (US$84–98 billion) in 2025, and authorities have launched a 60 billion-yuan (US$8.2 billion) fund to feed the early-stage pipeline. The result is a dense mesh of cloud options, accelerator vendors, and model providers prepared to court universities with localized pricing in Southeast Asia. Crucially, much of this capacity arrives physically nearby: Chinese cloud providers are building and leasing facilities across ASEAN, putting low-latency, compliant infrastructure within reach of public universities and vocational institutes that cannot afford U.S. hyperscaler pricing at commercial rates. The gravitational pull is not ideological; it is logistical.

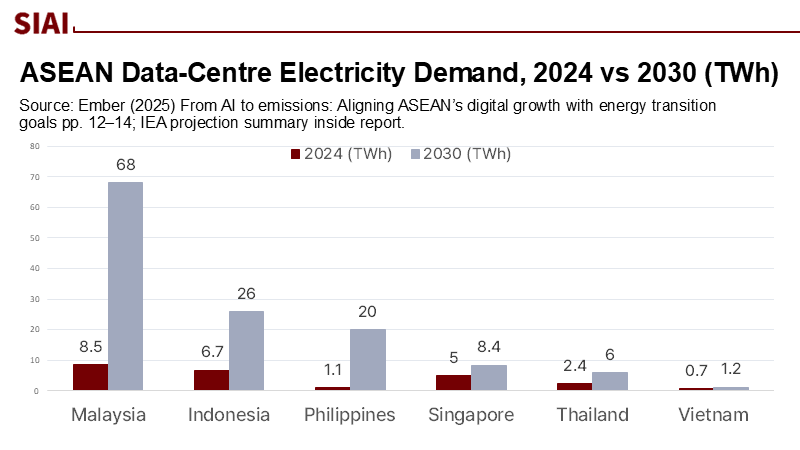

The infrastructure map supports that claim. Alibaba Cloud has opened a third data center in Malaysia and plans to open a second in the Philippines; Huawei Cloud and other Chinese providers are expanding across the region, even as they remain constrained in Western markets. On the demand side, ASEAN’s data-center electricity consumption is projected to nearly double by 2030, with Malaysia alone expected to surge from roughly 9 TWh in 2024 to about 68 TWh by decade’s end—a proxy for the compute that education and research could tap if access arrangements are negotiated early. The point is not that these facilities were built for universities, but that their presence expands the bargaining set for public procurement. Systems that move now can secure “education tiers,” a term referring to the levels of access and quality of services that can be obtained through early adoption of new technologies, while capacity is still being allocated.

Counterweights exist—and they matter. AWS has committed roughly US$9 billion to expand Singapore capacity by 2028, and Singapore-based GPU-as-a-service has begun offering H100-class clusters region-wide. That means ASEAN ministries are not condemned to single-vendor dependence; they can triangulate between the Chinese cloud in Malaysia/the Philippines, and an allied cloud in Singapore, weighting the mix by cost, latency, and export-control exposure. However, the real game-changer is bilateral recognition of credentials. This can significantly enhance cooperation and standardization, making the education-policy foundations for adoption more robust. On governance metrics, Oxford Insights places Malaysia, Thailand, Indonesia, and Vietnam in the region’s first tier of AI readiness; this is a signal—not a guarantee—that ministries can turn cloud capacity into curricular capacity if they move on teacher training and credential standards.

The Japan–Korea question should be read less as a capability deficit than as a pipeline constraint. Tokyo’s innovation-first AI Promotion Act gives universities a permissive legal frame for testbeds and industry partnerships; Seoul is pursuing scale, publicly targeting procurement of 10,000 high-performance GPUs to anchor a national AI center, while planning a substantial 2026 budget uplift oriented to AI-led growth. Aging demographics will result in tighter student cohorts and salary ladders. Still, in the near term, these systems can supply high-end practicums and faculty exchanges that ASEAN universities can plug into—especially if reciprocal recognition and cross-porting assignments are built into capstones.

What educators should do now: biliteracy, pooled computing, portable standards

The most valuable graduate over the next five years will not be a single-stack specialist but a “block-biliterate” engineer, teacher, or technician who can move fluently between the U.S./allied and Chinese stacks. That is not a rhetorical flourish; it is a curriculum blueprint. Start with the first-year “AI math labs” that teach probability, optimization, and numerical linear algebra alongside GPU programming. Add an intermediate year built around model-lifecycle assignments—data provenance, fine-tuning, safety evaluation—executed twice: once on a U.S./allied platform (CUDA/PyTorch, OpenAI-compatible APIs) and once on a Chinese/open alternative (Ascend/CANN, local API suites). In parallel, embed a shared safety card and documentation standard so that capstones travel. Singapore’s PISA record is instructive here: 41% of students hit the top tiers in mathematics; systems that choose high expectations and aligned supports can absorb technical content at pace. The takeaway is not to imitate Singapore, but to match its clarity on outcomes.

Compute is the binding constraint, so buy it like a region. ASEAN should pool demand for an education-only GPU bank that reserves capacity in Singapore (for allied-stack workloads) and in Malaysia/the Philippines (for Chinese-stack workloads), with a modest sovereign cluster in at least two mainland states for redundancy. The goal is not self-sufficiency; it is predictable access to mixed stacks at education prices. A three-year pooled reservation of a few thousand high-end accelerators—sourced across vendors—would support course-level quotas and research fellowships, with 15–20% capacity carved out for cross-border project teams and teacher-training colleges. The market context is favorable: capacity is being added quickly, and providers on both sides are seeking anchor tenants. If ministries commit early, they can secure telemetry and transparency clauses for model and data handling, and most importantly, price certainty for students.

Standards preserve mobility when politics does not. A narrow standards spine—dataset documentation, reproducibility checklists, incident reporting, and minimal safety tests—should be written once and made stack-agnostic, then embedded into procurement and accreditation. The BIS’s brief foray into controlling “model weights” underscored how quickly access rules can change, and how suddenly a project can become non-portable; ASEAN standards should assume volatility by design. Concretely, capstone projects should be graded on cross-portability: the same model must run on both stacks, with an identical artifacts bundle (weights if permissible, prompts, data sheets) escrowed locally with audit trails. Ministries need not invent all of this in-house; they can draw on existing research reproducibility norms and adapt them to undergraduate and TVET contexts.

The common critiques can be answered. “Isn’t this code for dependence on China?” Not if procurement is deliberately multi-homed and academic outputs must be cross-portable. “Won’t U.S. tariffs fade in court?” Perhaps—but today’s policy environment is already reshaping behavior, and even an adverse ruling in Washington won’t repeal the logic of export-control cycles or the sunk investments ASEAN states are making in nearby data centers. “Can Japan and Korea really anchor regional training if their cohorts shrink?” Yes, if ASEAN leverages them for advanced practicums and faculty exchanges rather than volume teaching. The deeper objection—that building biliteracy cedes ideological ground—misreads the purpose. The aim is not to normalize either stack; it is to teach students to translate between them, and thereby keep options open for the decade ahead.

Turning the agenda into procurement lines. Set three visible deadlines. First, publish a 12-course spine for block-biliteracy by mid-2026, with sample labs released under open licenses and an explicit mapping to TVET certificates and bachelor’s degrees. Second, negotiate an ASEAN Education Compute Facility that reserves capacity across at least three jurisdictions and two vendor families, with telemetry and queueing rules published up front. Third, issue micro-credential standards for “portable capstones” and agree on reciprocal recognition among willing ASEAN, Japanese, and Korean universities. The data-center boom is not a distant prospect; on most forecasts, ASEAN’s sector will double by 2030, and Malaysia’s power demand alone is slated for multi-fold growth. Education can contribute to that growth—but only if it moves while capacity is being allocated.

Where the money meets the model, the U.S. still leads in private AI investment by an order of magnitude; in 2024, U.S. private AI funding was roughly US$109 billion, nearly twelve times China’s US$9.3 billion. That gap indicates where cutting-edge tools will continue to emerge. But capital expenditure is a different variable: Beijing’s ¥600–700 billion AI capex this year pays for the hard things—compute, fabs, power, parks—that make access cheaper next door. For ministries, the lesson is to arbitrage the difference: teach on both stacks, research where you can secure credits and GPUs at scale, and align teacher training to the standards that travel regardless of geopolitics. If tariffs are the tax on indecision, then biliteracy is the hedge against it.

Implications for schools below the university tier. The split will reach secondary schools via content filters, cloud-delivered tutoring, and the identities of the firms that underwrite assessments and teacher PD. We should maintain universal and straightforward guardrails: privacy-preserving analytics, dataset provenance in plain language, and a relentless emphasis on statistical thinking over rote “prompting.” In systems that can afford it, a small, ring-fenced share of pooled compute should be dedicated to teacher colleges and vocational institutes; the payoff is immediate, as industry utilizes the graduates these institutions produce. When procurement officers ask whether such ring-fences are realistic in an era of energy-hungry data centers, point to the region’s expansion numbers and the rise of GPU-as-a-service: capacity is growing, and governments retain leverage if they buy together and publish usage telemetry.

What matters now is that the temptation is to wait for the litigation cycle to conclude and for export-control guidance to be finalized. However, higher education does not operate on quarterly horizons; it operates on cohort horizons. A student who starts a diploma in 2026 will graduate into a world of stacked toolchains and political contingencies. The systems that act now—designing biliterate curricula, buying pooled compute, and locking in portable standards—will ship graduates who can work anywhere, with anyone, on anything that meets baseline safety and documentation. The systems that delay will inherit syllabi tied to whichever vendor offered a quick discount in 2024–2025, and will spend the next decade unpicking those decisions. The policy north star is not autarky; it is freedom to choose, class by class and project by project. That is what sovereign education looks like in a blocked world.

We began with two numbers: a tariff floor and a capex surge. The first is already rewriting procurement spreadsheets and cross-border contracts; the second is already reshaping where ASEAN’s compute sits and who can afford to rent it. Treat the combination as an opportunity, not a trap. Ministries should commit—before this academic year ends—to a biliterate spine that forces students to ship on both stacks; to a regional GPU bank that buys time, literally, for classrooms; and to a minimalist standards passport that keeps work portable no matter how court rulings or export rules swing. The U.S. investment engine will keep throwing off new tools; China’s industrial machine will keep laying concrete and cables; and ASEAN’s data-center curve will keep racing upward. If educators act now, they can transform tariff noise into a valuable human capital signal. The right graduates—fluent in both dialects of AI, trained on shared standards, comfortable switching stacks—will insulate schools from politics by making their students indispensable to both sides. That is how public education converts a trade shock into a decade of strategic advantage.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Alibaba Cloud. (2025, July 1–3). Third Malaysia data center; second in the Philippines (October plan). Reuters; DataCenterDynamics; Economic Times.

Bureau of Industry and Security (U.S.). (2025, Jan.–Feb.). Interim Final Rule on advanced computing ICs and AI model weights; associated summaries and client alerts. Sidley; Covington; KPMG; Freshfields;

Ember. (2025, May 27). From AI to emissions: Aligning ASEAN’s digital growth with decarbonisation (report and web chapter).

Future of Privacy Forum & IAPP. (2025, Jun.–Jul.). Japan’s AI Promotion Act: Innovation-first governance.

Oxford Insights. (2024–2025). Government AI Readiness Index 2024 (report and ASEAN brief).

OECD. (2023–2024). PISA 2022: Country notes—Singapore; Volume I.

Reuters. (2025, July 2). Alibaba Cloud expands in Malaysia and the Philippines.; (2025, Jun. 18). Malaysia data-center power demand outlook.; (2025, Aug. 21–29). South Korea budgets for AI-led growth.

Reuters / Fortune / Tech in Asia. (2025, Feb. 16–18). South Korea aims to secure 10,000 GPUs for a national AI center.

Singtel. (2024). GPU-as-a-Service initiatives (H100 clusters) and Nscale partnership.; WSJ coverage.

South China Morning Post; TechWireAsia; Tech in Asia. (2025, June–July). China’s AI capex forecast at US$84–98 billion; launch of 60 billion-yuan AI fund.

Stanford HAI. (2025). AI Index 2025: Private investment by country (U.S. $109.1B vs China $9.3B in 2024). (PDF and Economy chapter).

U.S. Executive Office. (2025, Jul. 31). Further Modifying the Reciprocal Tariff Rates (Executive Order 14257 background).

Washington Post & Wall Street Journal. (2025, Sept. 4). Administration seeks Supreme Court relief to sustain global tariffs.

Wire services (Reuters). (2025, Sept. 3). EU official confirms 15% U.S. tariff rate context and flows under new deal.

Similar Post

Tariffs Are Taxes—And the Bill Lands at Home

Tariffs act as hidden taxes, falling mainly on U.S.

The Political Economy of Masculinity Norms: Why Identity Still Moves Markets and Classrooms

Masculinity norms shape labour supply, health, and political preferences Germany’s 1940s and Korea’s 2020s show contrasting trajectories Education policy can recalibrate norms and stabilise economies